Consider this scenario. You’re driving home from work after a busy shift and there has been an accident ahead on the freeway. As you approach, you see that a vehicle has been rear-ended, causing a fire. The occupant of the car, an elderly man, is sitting on the side of the road. He looks shaken, but tells you his name and asks you to call his wife. He has visible burns to his face, neck, upper chest, and both arms. Do you know what the first priorities are for assisting this man?

Each year in the United States 3,400 people die from burns and smoke inhalation and 450,000 patients require treatment for burn injuries. Burns are among the most devastating and life changing of injuries because of the unpredictable nature of the initial wound(s), the overwhelming systemic inflammatory response, and the potential need for extensive rehabilitation and psychosocial adaptation. Burn injuries involve multiple etiologies, and the initial treatment required varies with each. (See Burn etiologies.)

Emergency burn response: Following the ABCDEs

The first hours after a burn injury occurs are a critical time. Decisions made and treatments rendered during this time can mean the difference between life and death. In 2012 the American Burn Association’s (ABA) Advanced Burn Life Support (ABLS) course included revised guidelines for emergency burn care. ABLS is a comprehensive 8-hour course that covers initial assessment and management of burns, evaluation of burn size, fluid resuscitation, transport guidelines, and other topics pertinent to emergency burn treatment in the first 24 hours after a burn injury.

Burns vary in size (percentage of total body surface area burned) and severity (depth) based on temperature and time of exposure to the burn source. Familiarize yourself with the appearance of first, second, third, and fourth degree burns, shown in the images below. Note the remarkable differences in appearance based on severity/degree of burn.

Severity of burnsSource: Images are used with permission of the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX. |

It’s important to recognize that the first priority for burn patients is not the treatment of the wound. This can be a difficult concept to understand because burn injuries may be visually distracting and extremely painful for the patient. Rather, the priority is to implement the ABCDE approach, a methodical response that ensures life-threatening complications of burn emergencies are addressed rapidly and effectively. (See The ABCDEs of emergency burn care.)

The ABCDEs of emergency burn careAirway maintenance with cervical spine protection Breathing and ventilation Circulation and cardiac status with hemorrhage control Disability, neurological deficit, and gross deformity Exposure to Examine for major associated injuries and maintain warm Environment Source: American Burn Association. Advanced Burn Life Support course provider manual. Chicago, IL: American Burn Association; 2011. |

Airway evaluation and maintenance with cervical spine protection must always be your first priority. It is also important to protect the cervical spine if there is obvious or suspected traumatic injury. Burn patients frequently become edematous because of the marked increase in capillary permeability, which occurs as a response to the burn injury. Edema is a frequent culprit in compromising the airway of burn patients. Therefore, once emergency medical services (EMS) have arrived, intubation will be required if the airway is compromised.

Breathing and ventilation is the next step. Burns of the chest may restrict the expansion of the chest wall because of the stiffening of the dermis in deep burns, which can impact respirations. Inhalation of smoke impairs gas exchange (oxygen and carbon dioxide) at the alveolar level. Any patient with suspected smoke inhalation injury must be started on high-flow oxygen (15 L/min at 100%) using a non-rebreather oxygen mask. You should suspect an inhalation injury if the fire occurred in an enclosed space, if the patient has singed nasal hair, facial hair, or both, or soot around the nose/mouth. Keep in mind, however, that respiratory distress can also be caused by a condition not related to the burn, for example, a patient with preexisting diagnoses such as congestive heart failure or asthma.

Circulation and cardiac status (with hemorrhage control in cases of trauma) is the third step in the emergency burn care process. In addition to evaluating the patient for hemodynamic stability, it is important to remember that edema can impair peripheral circulation. Your assessment may include evaluation of heart rate, peripheral pulses, and skin color (of unburned skin). Prehospital personnel will insert large-bore I.V. catheters for fluid administration. Larger burns will require high volumes of continuous I.V. fluids to accommodate for the shift of plasma into the interstitial tissue, which occurs as part of the physiological response to burn injury.

Disability, the fourth priority in the ABCDE evaluation, refers to neurologic deficit and gross deformity. Once again, keep in mind that a trauma injury may result in deformities such as open fractures. When this happens, these traumatic injuries must also be included in your assessment and treatment. Neurological assessments must be performed. With the exception of smoke inhalation, burns should not necessarily affect the level of consciousness. Therefore, if you assess altered level of consciousness, consider other problems such as head trauma, carbon monoxide poisoning, hypoxia, preexisting medical conditions, or substance abuse.

The fifth and final step in the emergency burn care process is Exposure to examine for major associated injuries and maintaining a warm environment. Remove any clothing or jewelry that is restrictive or covering the body part that was burned. Quickly look for other injuries and then cover the patient. If the patient is wearing contact lenses, these should be removed immediately to prevent corneal damage from edema. You may cool the burn with water for a few minutes.

Never use ice or cold water because it will restrict peripheral circulation locally, increasing the depth of the burn, and it may decrease body temperature. It is imperative to prevent hypothermia in burn patients, as body temperatures below 97.7° F (36.5° C) in the first 24 hours are associated with increased mortality. Cover the patient with a clean, dry covering such as a sheet or blanket to prevent evaporative heat loss.

Burn center referral

There are 90 to 100 hospitals with burn centers in the United States. Verified burn centers have specially trained staff and resources. The ABA and the American College of Surgeons perform rigorous criteria-driven evaluations to ensure that verified burn centers are able to provide burn care throughout the continuum of care, from acute injury to rehabilitation. The ABA also describes patients who should be referred to a verified burn center for definitive care. As a nurse, you should familiarize yourself with these criteria. (See Burn center referral criteria.)

Burn center referral criteria

Source: American Burn Association. Advanced Burn Life Support Course Provider Manual. Chicago, IL: American Burn Association; 2011. |

Putting it all together

Let’s return to the scenario of the car accident at the beginning of this article. Your own safety is of the utmost importance. Be sure to evaluate the scene carefully for fires that may not be extinguished, debris, or other dangers before you approach. The first two priorities for the elderly man are airway and breathing. You’ll keep him sitting upright, which may help decrease edema formation to the face and neck, preserving the airway. Observe the patient for respiratory effort and symmetrical chest wall expansion. When prehospital personnel arrive on the scene, you can anticipate that they will administer high-flow oxygen. Intubation may also be needed to protect and maintain the airway. Check pulses in affected extremities. Report your findings to the responders. You can anticipate that two large-bore I.V.’s will be placed and I.V. fluids started immediately. Although the patient may be alert and oriented now, you should monitor closely for any changes. Check the patient’s jewelry and clothing and gently remove anything that may be restricting circulation, keeping in mind that the patient may develop edema later. If you or a passerby has a clean blanket or sheet in your vehicle, cover the patient to maintain a warm environment.

Once the patient has been transported and stabilized at the closest emergency department, you can anticipate that he will be referred to a specialty burn center because the case satisfies at least three important criteria:

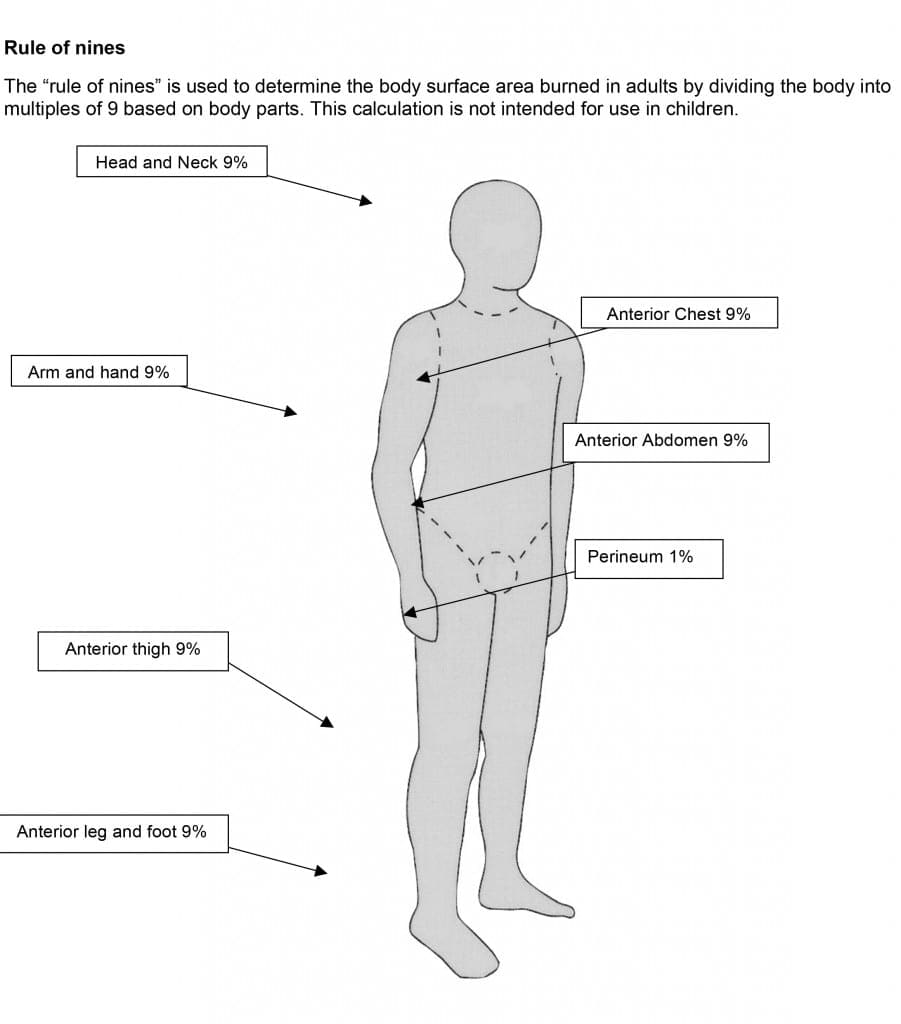

- There are burns to the patient’s face, neck, upper chest, and both arms, encompassing more than than10% of his total body surface area (See Rule of nines.)

|

- The burns involve critical functional areas (face, hands, and over major joints).

- The patient may also require significant rehabilitation due to his age.

Promote positive outcomes

Following the ABCDEs of emergency burn response will help you promote positive outcomes for burn patients you may encounter. For further information about burns and ABLS courses in your area, contact the American Burn Association at ameriburn.org.

Selected references

American Burn Association. Advanced Burn Life Support Course Provider Manual. Chicago, IL: American Burn Association; 2011.

American Burn Association. Burn care facilities. www.ameriburn.org/BCRDPublic.pdf.

American Burn Association. Burn incidence and treatment in the United States: 2013 fact sheet. www.ameriburn.org/resources_factsheet.php.

Heffernan JM, Comeau OY. Management of patients with burn injury. In: Hinkle JL, Cheever KH, eds. Brunner & Suddarth’s Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:1805-1836.

Hostle D, Weaver MD, Ziembicki JA, et al. Admission temperature and survival in patients admitted to burn centers. J Burn Care Res. 2014;34(5):498-506.

Jamie M. Heffernan is the patient care director of the New York Presbyterian William Randolf Hearst Burn Center in Manhattan, and Odette Y. Comeau is an adult critical care clinical nurse specialist at University of Texas Medical Branch.

1 Comment.

Very interesting course