When registered nurse Andrea arrives on shift for report, she learns that her patient, a 62-year-old male, has a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC). As she starts to assess him, she sees a double-lumen catheter in his chest. When she asks a coworker how to identify and care for this line, she hears baffling instructions about tip placement, along with some terms she’s not sure of, such as power injection, valved, and tunneled.

Andrea isn’t the only nurse who might be at a loss in this situation. Central catheters can be confusing. To help clarify this important topic, this article compares the various types of central catheters and explains how to identify, care for, and maintain them. Although central catheters used in pediatric patients are similar to those used in adults, this article focuses on adults.

Types of central catheters

Central catheters are identified by location, type, indication, and tip location. Types of central catheters include:

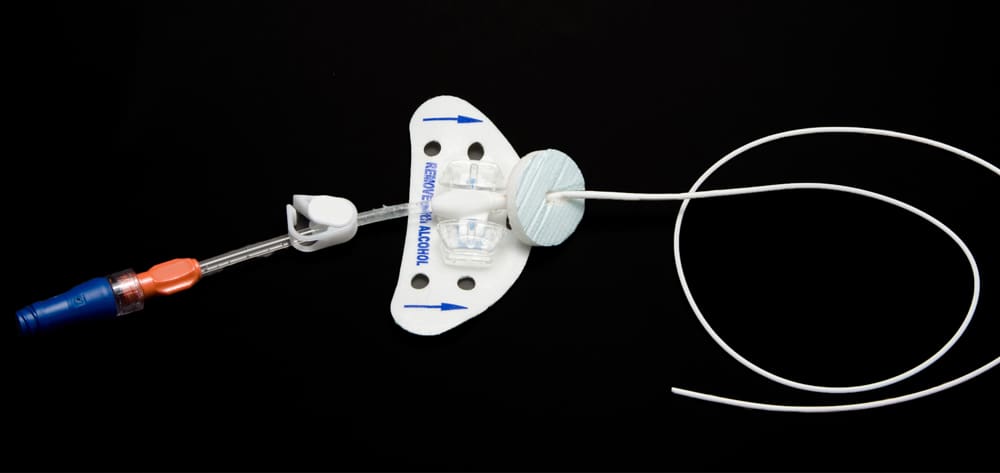

- PICCs; inserted into the patient’s arm with the tip terminating in the superior vena cava, these may be indicated for both short- and long-term therapies (up to 1 year or so)

- nontunneled catheters

- tunneled catheters

- implantable ports

- dialysis catheters.

Also, a central catheter may be open-ended or valved, and it may or may not be power injectable. Catheters also vary in number of lumens (from one to four) and in French size (4 to 14 Fr), with either a straight or reverse taper on the distal portion. Tapered catheters are wider at the insertion site, in essence plugging the larger-insertion puncture site to lessen bleeding. Some clinicians prefer a tapered catheter, using the catheter or a dressing technique to stop bleeding at the insertion site.

The type of catheter used depends on the therapy required (such as total parenteral nutrition, lipids, or multiple antibiotics) and patient characteristics (for instance, the need for a central catheter versus a less invasive peripheral line). Each catheter type has risks and benefits, which clinicians must discuss with patients when planning care.

Once the clinician determines the patient needs a central catheter, the next decision is how many lumens the catheter should have. Central catheter placement using ultrasound allows measurement of the patient’s vein size, which ensures an appropriate-size catheter to allow blood to flow around it. A catheter that’s too large can cause arm swelling and deep vein thrombosis.

Nontunneled catheter

A nontunneled catheter typically is inserted in the neck, chest, or groin using the internal jugular or subclavian vein or, in emergencies, the femoral vein. If the patient is chronically ill or other veins are hard to access, the catheter may be placed in another vein, such as the translumbar vein.

Indicated for acute short-term conditions, nontunneled catheters come with single, double, triple, or quadruple lumens and in multiple sizes (14 to 22 G). The Centers for Disease Control and Preven-tion (CDC) doesn’t recommend their routine replacement. Patients should be assessed daily to determine if they still need the catheter; it should be removed as soon as it’s no longer needed.

Tunneled catheter

A tunneled catheter must be inserted invasively to help secure it and promote longevity. It has a cuff that stimulates tissue growth and helps hold the catheter in place; the catheter is positioned with the cuff 2 to 4 cm from the insertion site. A retention suture sometimes is used to hold the catheter until the tissue grows around this cuff, which takes 1 to 4 weeks. The remaining catheter portion is exposed but provides external access to eliminate needle sticks. The exposed portion requires daily to weekly maintenance and must be protected from being pulled or getting wet.

Implantable port

An implantable port (also called a portacath or subcutaneous implanted port) is attached to a reservoir. The entire catheter and reservoir are placed surgically or locally beneath the skin, allowing the patient to shower and bathe without restrictions. Implantable ports come with single and dual lumens. To access the catheter, the skin is pierced with a special noncoring needle.

Dialysis catheter

Not used routinely for access, a dialysis catheter may be used in a life-threatening emergency if no other access is available. It’s inserted in the neck or chest through the internal jugular or subclavian vein (or in some cases, the femoral vein). It may be tunneled or nontunneled, depending on urgency of need, patient’s diagnosis, and expected duration of use. Nontunneled dialysis catheters are used for short-term acute treatment or until a more permanent tunneled catheter can be placed. Some manufacturers have added an extra lumen to allow I.V. medication administration; this lumen requires the same maintenance as any central-catheter lumen.

A dialysis catheter is accessed, cleaned, and flushed differently than other catheters; this article doesn’t address those topics. If your patient has a dialysis catheter, assess the site carefully to check whether the dressing is clean, dry, and intact. Be aware that in some facilities, a dialysis catheter is packed with a solution, such as normal saline solution, citric acid, alteplase, or large heparin doses. When the catheter is accessed, the packing solution must be removed first; afterward, the dialysis team (or other specialty team) must be called to repack the catheter.

Care and maintenance

Care and maintenance of a central catheter requires vigilance and attention to detail to prevent complications and maintain patency. More than 80% of bloodstream infections are linked to vascular access devices, and 50% of these infections are preventable. Various organizations provide guidelines on central-catheter care. (See Organizations with central-catheter care guidelines by clicking the PDF icon above.)

The Institute for Health Care Improvement (IHI) recommends bundling multiple practices to improve patient outcomes and prevent central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). Components of the IHI central-line insertion bundle include:

- hand hygiene

- maximal barrier precautions, including a large sterile drape covering the patient head to toe (with a small opening at the insertion site) and head covers, masks, sterile gowns, and gloves for all personnel directly involved in line insertion

- chlorhexidine skin antisepsis at the insertion site

- optimal site selection; the inserting clinician reviews risks and benefits of line placement in the various veins

- daily review of the need to continue the central catheter.

Central catheter maintenance involves some of the same components as the insertion bundle but includes additional components.

Hand hygiene

Perform hand hygiene before and after every patient contact. If you enter the patient’s room to care for the catheter or administer drugs through it but will perform other activities beforehand (such as changing the dressing or providing indwelling urinary catheter care), rewash your hands before you touch the catheter. Recommendations for achieving National Patient Safety Goals for infection prevention include proper hand hygiene, setting goals for improving hand hygiene, and using proven guidelines to prevent CLABSIs.

Skin antisepsis

Skin antisepsis at the insertion site is crucial to CLABSI prevention. Disinfect the skin with an appropriate antiseptic at each dressing change. The CDC recommends a chlorhexidine preparation stronger than 0.5% in 70% isopropyl alcohol. Scrub back and forth for 30 seconds and let the site dry completely (which may take 30 seconds to 3 minutes). Don’t apply the dressing until the preparation has dried, to avoid skin irritation and redness under the dressing. If the patient can’t tolerate chlorhexidine, clean the skin with tincture of iodine, an iodophor preparation, or 70% isopropyl alcohol.

Dressing changes

The dressing at the insertion site helps protect the catheter. Frequency of dressing changes depends on dressing type and integrity. Change a transparent dressing every 7 days; change a gauze dressing every 48 hours.

If the dressing is no longer intact, is oozing, or has become bloody or contaminated, change it as soon as possible. Apply an impermeable cover before the patient takes a shower or bath to protect it from direct contact with water. Manufacturers make covers specifically for central catheters to keep dressings dry in the shower. If the dressing gets wet and is no longer intact, change it to prevent infection.

Chlorhexidine sponges or dressings and silver patches provide continued antisepsis under the dressing. If your facility’s central catheter infection rate hasn’t decreased despite adherence to ba-sic prevention measures, use a chlorhexidine-impregnated sponge for temporary short-term catheters in patients older than 2 months, per CDC recommendations.

Securement-device changes

A central catheter must be stabilized to prevent dislodgment, migration, damage, and pistoning (back-and-forth motion within the vein, which can damage the intima and cause phlebitis and infection). Many physicians suture catheters in place to stabilize them and prevent malpositioning. Clean the sutures when changing the dressing, noting skin redness around them. Reddening may warrant suture replacement with a sutureless-securement device, which can help prevent catheter malpositioning and pistoning. Replace securement devices during dressing changes.

Tubing changes

Be sure to prime the administration set and maintain infusate sterility. Know that nonvented administration sets are used for I.V. bags; vented administration sets, for solutions in glass bottles (such as propofol).

Frequency of tubing changes depends on whether the infusion is intermittent or continuous. For continuous medication or fluid infusions, don’t disconnect the tubing from the patient; change it every 72 to 96 hours. If the patient’s receiving intermittent infusions (such as one or two daily doses of an antibiotic), the tubing can be disconnected. Tubing that’s disconnected from the patient or the main I.V. tubing is considered intermittent and should be changed every 24 hours to decrease contamination risk.

Blood, parenteral nutrition, and fat emulsion fluids have separate requirements for tubing changes. According to the American Association for Blood Banks, red blood cell components expire 4 hours after the catheter is accessed when transfused through a 170- to 260-micron filter. If one unit of blood takes 4 hours to infuse, change the tubing before starting the second unit. Follow your facility’s policy for tubing changes with blood products.

The Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition provides guidelines for tubing changes through a catheter used to administer lipids and parenteral nutrition. It recommends changing the tubing:

- every 12 hours for lipid products

- every 24 hours for parenteral nutrition products with lipids or that have a Y-connection for lipids

- every 72 to 96 hours for parenteral nutrition without lipids.

Changing and cleaning the cap

An almost-forgotten component of central-catheter care is changing the I.V. cap. CDC recommends changing the cap with a tubing change no more often than every 72 hours. The Infusion Nurses Society recommends changing the cap every 7 days with a dressing change. Both organizations recommend changing a cap that is clotted or contaminated.

Cap changes can be confusing when the tubing is changed every 12 to 24 hours. No evidence exists on the practice of changing caps with each tubing change; check your facility’s policy and procedures. Some facilities may require cap changes every 12 to 24 hours, others every 72 to 96 hours, and some with each dressing change. Also, check the manufacturer’s guidelines; some manufacturers recommend changing the cap after blood withdrawals.

When changing the cap, be sure to prime the new cap with saline solution and clean the catheter hub. Despite the minimal flush volume of I.V. caps, introducing air into the line puts the patient at risk for air embolism. (See Cleaning the hub by clicking the Pdf icon above.)

Flushing the catheter

The catheter must be flushed to maintain patency. Otherwise, it becomes sluggish, blood return is impeded, and blood and medication build up on the inside of the catheter, forming fibrin. Fibrin can act as a barrier inside and around the catheter, leading to occlusion. Also, pathogens cause development of biofilm, which can lead to catheter malfunction and infection.

All central catheters should be flushed with normal saline solution before and after medication administration. Flushing frequency varies with catheter type. Nonvalved catheters require more frequent flushing, with recommendations varying from every shift to every day. Follow your facility’s guidelines on flushing frequency. Valved catheters require once-weekly flushing when not being used to administer fluids or medications. Failure to flush between medications can cause catheter occlusion from precipitate formation.

For routine flushing, use 10 mL normal saline solution. When withdrawing blood specimens through the catheter, flush with 20 mL. If your patient’s receiving viscous solutions (such as lipids or parenteral nutrition), flush with 20 mL normal saline solution. Check your facility’s policy and procedure on the amount and frequency of saline flush to use for these therapies. (See Heparin versus saline flush by clicking the Pdf icon above.)

The flushing method depends on the type of catheter cap (positive-pressure, neutral, or negative-pressure) and certain other features. For instance, some catheters lack clamps. Negative-pressure caps require clamping before syringe removal. Neutral caps may or may not require clamping but should be clamped before syringe removal. Positive-pressure caps don’t require clamping; if your facility recommends clamping the catheter, clamp it after syringe removal. Follow the manufacturer’s recommendations for flushing and clamping.

If you meet resistance during flushing or don’t see a blood return, assess catheter patency before administering medications and fluids. Don’t flush the catheter forcibly. Aspirate for a blood return to confirm patency before administering medication and solutions and during every shift. If blood return is absent, assume the catheter is malpositioned or an occlusion has formed, which calls for declotting medication. Either complication requires assessment and intervention.

Competent catheter care

Competent, confident central-catheter care and maintenance can help prevent dangerous complications that imperil a patient’s life. Make sure to follow catheter-care recommendations from relevant organizations and catheter manufacturers. For information about complications of central catheters, read “Recognizing, preventing, and troubleshooting central-line complications” in the November 2013 issue of American Nurse Today.

Selected references

American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Safe practices for PN. 2004. Accessed March 6, 2014.

Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, et al.; Clinical Transfusion Medicine Committee of the AABB. Red blood cell transfusion: A clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):49-58.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI). Last updated May 17, 2012. www.cdc.gov/hai/bsi/bsi.html. Accessed March 6, 2014.

How-to guide: Prevent central line-associated bloodstream infection. Institute for Healthcare improvement. 2012.

www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/HowtoGuidePreventCentralLineAssociatedBloodstreamInfection.aspx. Accessed March 6, 2014.

Infusion Nurses Society. Infusion nursing standards of practice. J Infusion Nurs. 2011;

34(suppl 1):S1-S109.

Joint Commission, The. Hospital: 2014 National Patient Safety Goals. 2014. www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2014_HAP_NPSG_E.pdfx. Accessed March 6, 2014.

McNair PD, Luft HS. Enhancing Medicare’s hospital-acquired conditions policy to encompass readmissions. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2(2):E1-E15. www.cms.gov/mmrr/Articles/A2012/mmrr-2012-002-02-a03.html. Accessed March 6, 2014.

O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al.; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections, 2011. www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/guidelines/bsi-guidelines-2011.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2014.

Rupp ME, Yu S, Huerta T, et al. Adequate disinfection of a split-septum needleless intravascular connector with a 5-second alcohol scrub. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(7):661-5.

Schallom ME, Prentice D, Sona C, Micek ST, Skrupky LP. Heparin or 0.9% sodium chloride to maintain central venous catheter patency: A randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(6):1820-6.

Ann Earhart is a vascular and infusion clinical nurse specialist at Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix, Arizona.