Martha Johns is admitted to the acute-care medical unit for monitoring and I.V. antibiotics to treat community-acquired pneumonia. Since her admission, her respiratory rate has ranged from 10 to 24 breaths/minute. Her white blood cell count remains elevated at 16,000 cells/mcL and her temperature is 96.6° F (35.9° C). When she becomes confused, the nurse increases her supplemental oxygen flow from 2 to 6 L/minute gradually over 2 hours to keep her pulse oximetry reading (SpO2) above 92%.

David Chao was admitted to the acute-care surgical unit 2 days ago after ventral hernia repair. His vital signs have been stable and within normal ranges. But during the afternoon assessment, the nurse notes his heart rate has increased to 110 beats/minute (bpm) and his respiratory rate has risen slightly to 22 breaths/minute. He reports he hasn’t had to use the urinal since early in the morning.

If you care for medical-surgical patients, you’re probably familiar with scenarios like these. When a patient’s assessment findings change as they did for Mrs. Johns and Mr. Chao, ask yourself, “Could this clinical change represent sepsis development or a deterioration related to severe sepsis?”

At hospitals across the country, sepsis education is increasing, and more clinicians are using a systems approach for early sepsis identification and timely evidence-based interventions for patients with suspected or known sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock. These sweeping changes stem largely from the work of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) and hospitals’ commitment to reduce unacceptably high sepsis-related deaths. A collaboration of expert clinicians from critical-care professional organizations, SSC aims to reduce sepsis-

related deaths worldwide through awareness building, clinician education, development of diagnostic and management guidelines, and performance-improvement programs.

This article presents an overview of sepsis, reviews current recommendations from SSC’s updated guidelines for managing severe sepsis and septic shock, and describes one hospital’s approach to early detection and management to reducing sepsis-related deaths.

Understanding sepsis terminology

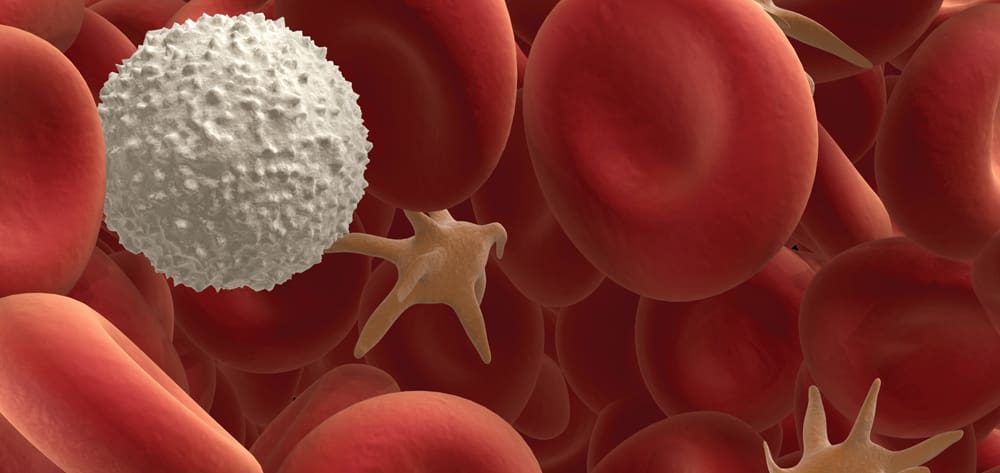

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome with a continuum of increasingly severe manifestations. The term refers to the body’s response to an infection that has moved beyond localized tissue to become systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). In SIRS, signs and symptoms result from systemic activation of the immune response to an infection or an injury (such as trauma or acute pancreatitis). SIRS manifestations include tachycardia, tachypnea or hyperventilation, body-temperature changes, and leukocytosis or leukopenia.

Unless identified and treated early, sepsis can progress to severe sepsis, which causes signs and symptoms of organ dysfunction or tissue hypoperfusion. Septic shock, at the far end of the sepsis continuum, is severe sepsis accompanied by persistent hypotension after fluid resuscitation. (See Sepsis terms and definitions by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Managing severe sepsis and septic shock

Because early sepsis identification allows prompt diagnosis and management, the 2012 SSC guidelines recommend hospitals implement a performance-improvement program for sepsis, including a routine patient-screening process for severe sepsis. The guideline for managing severe sepsis and septic shock specifies two care bundles. The first bundle should be completed within 3 hours of severe sepsis presentation; the second bundle, within 6 hours. (Note: The Institute for Healthcare Improvement calls the first bundle the severe sepsis 3-hour resuscitation bundle; the second bundle, the 6-hour septic shock bundle.)

3-hour bundle

Within the first 3 hours, healthcare providers should:

- obtain blood lactate levels to identify possible tissue hypoperfusion related to severe sepsis and to evaluate resuscitation interventions. A byproduct of anaerobic metabolism, lactate occurs in sepsis when oxygen demand exceeds oxygen delivery to tissues.

- perform appropriate diagnostic tests (including blood cultures) before giving antibiotics, to aid prompt diagnosis. Barriers to this recommendation include challenging vascular access, variations in access to phlebotomy services or nurse phlebotomy skills, and competing patient-care priorities related to sepsis management. At the University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center (UCSFMC), we found that using a blood culture algorithm with a timeline and escalation options reduces the median time for obtaining blood cultures.

- administer broad-spectrum antibiotics within 1 hour of recognizing severe sepsis or septic shock. To prevent administration delays, standard broad-spectrum antibiotics recommended by the UCSFMC pharmacy are stocked in medication stations on all inpatient units.

- administer crystalloid I.V. fluids totaling 30 mL/kg (2,400 mL for an 80-kg patient) when the patient has hypotension or a lactate level of 4 mmol/L or higher. At UCSFMC, we’ve encountered such challenges as the time providers take to weigh the risks and benefits of administering fluids to patients with cardiac insufficiency, as well as comorbidities that raise concern for harmful effects of fluid overload.

6-hour bundle

The second bundle typically relates to the patient’s transition to a higher level of care. Healthcare providers should administer vasopressors if hypotension persists after the initial 30 mL/kg fluid resuscitation. The goal is to achieve a target mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 65 mm Hg or higher. SCC guidelines recommend remeasuring lactate levels to evaluate the effects of fluid or vasopressor resuscitation (or both), as well as measuring central venous pressure (CVP) and central venous oxygen saturation (Scvo2) in patients with septic shock to guide further interventions.

Be aware that CVP and Scvo2 measurements require an invasive central venous catheter. Also, the usefulness of CVP and Scvo2 monitoring is controversial; studies are underway to evaluate their clinical efficacy. Results of these studies will provide evidence addressing the controversial points and update the evidence-based recommendations in SSC guidelines.

Scenarios continued

When the nurse reassesses Mrs. Johns, he notes signs of severe sepsis and suspects her condition is worsening. He obtains a blood lactate level per the protocol and notifies the physician of the change in her condition and her lactate level of 5.3 mmol/L. The new assessment and lab findings trigger activation of the Code Sepsis system, leading to prompt blood culture sampling, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and an I.V. fluid bolus of 30 mL/kg. The nurse closely monitors the patient’s hemodynamic and respiratory response and obtains a follow-up lactate level.

When obtaining new vital signs for Mr. Chao, the nurse finds a heart rate of 130 bpm and blood pressure of 88/60 mm Hg. After the patient complains of new abdominal pain, she notifies the physician and communicates her concern that he might have severe sepsis. Per protocol, she obtains a blood lactate sample; the lab calls to report a critical level of 4.8 mmol/L. After activating the Code Sepsis system, she obtains blood cultures and begins an I.V. fluid bolus of 1.5 L, as ordered. When Mr. Chao’s blood pressure remains low, he is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), where he’s started on antibiotics and receives an additional fluid bolus. Also, a norepinephrine infusion is started, titrated to keep his MAP above 65 mm Hg.

In both of these cases of patients with known infections who are receiving treatment, the nurse adeptly detected a decline in the patient’s condition along the sepsis continuum.

UCSFMC sepsis initiative

The sepsis initiative at UCSFMC launched in January 2012 with the goal of reducing sepsis-related deaths. It uses a systems approach to ensure early detection and timely management of severe sepsis and septic shock. The following sections describe the actions of the interprofessional team in educating clinicians, designing and testing a sepsis screening tool and electronic alert system, and improving systems to promote rapid management of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock.

Interprofessional team

We started the initiative by convening an interprofessional sepsis committee consisting of clinical and advance practice nurses, physicians, pharmacists, and representatives from the laboratory and quality and safety program. The emergency department (ED), medical-surgical ICU, progressive care unit, and medical acute-care unit were chosen as pilot units because they frequently have sepsis cases. Physician and nurse champions from those units worked closely with the sepsis committee to determine screening criteria and operational definitions, design sepsis screening tools, plan education for pilot-unit clinicians, and outline the sepsis management bundle in concordance with SSC guidelines. The champions served as unit- and discipline-based resources, participated in design and testing of new tools, and represented peer feedback in the performance-improvement process.

Clinician education

To raise sepsis awareness and provide education on sepsis diagnosis and treatment, UCSFMC offered clinicians several educational opportunities:

- nursing grand rounds

- nursing stories from the bedside session dedicated to sepsis education and case studies coinciding with World Sepsis Day

- case-based, high-fidelity, hands-on simulation sessions with interprofessional participation

- online educational modules and educational staff development at staff meetings

- unit-based newsletter articles and educational posters and flyers.

Sepsis screening

One of our goals was to implement an electronic surveillance system for early sepsis detection that would continually evaluate patients for signs of sepsis as new data populated the medical record. While this system was being built and tested, a paper screening system was designed and implemented on the inpatient pilot units. Nurses completed the paper screening at least once each shift and with clinical changes, as needed.

Electronic surveillance and alerts

The ED moved forward with sepsis surveillance and electronic alerts. The electronic surveillance system included decision-support algorithms to activate the Code Sepsis response system and aid completion of sepsis bundle interventions. Screening systems were validated through review of completed screening tools and charts.

After a year of design and testing by unit champions, inpatient pilot units began electronic sepsis surveillance using the electronic medical record (EMR). To design the inpatient system, we built on our experience with ED surveillance and alerts. The electronic surveillance system evaluates clinical documentation, including laboratory results, and triggers a pop-up window alert if data meet configured sepsis criteria. Healthcare providers (including physicians, nurses, and physician assistants) and pharmacists receive activated electronic alerts when they open the EMR.

Links within electronic alerts promote use of the lactate protocol, which was developed to allow a nurse-driven order for a lactate laboratory test based on specified sepsis criteria. Also, a standardized electronic sepsis order set was developed and made accessible to all providers, to promote timely ordering of management bundle elements. (See Designing an electronic surveillance and alert system by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Code Sepsis response system

We implemented a Code Sepsis response system to bring trained resources to the inpatient pilot units and thus reduce delays in sepsis detection and management. Nurses activate a Code Sepsis through hyperlinks in the electronic alerts or through the pager system. Code Sepsis team members who respond to manage patients meeting severe sepsis or septic shock criteria include the rapid response team (RRT) nurse and respiratory therapist, a critical care nurse practitioner (NP), and a pharmacist providing remote consultation. The NP serves as the Code Sepsis team leader and ensures that sepsis management bundle elements are implemented in a timely manner as indicated.

Challenges

To determine if a patient has a sepsis condition, electronic alerts prompt UCSFMC nurses to answer a question to determine if clinical changes relate to an infection. Our nurses found this question challenging to answer, as most of their patients were at risk for infection but had many other medical or surgical conditions that could explain the clinical change. We gathered their feedback on ways to improve the system. For instance, we asked, “Looking back on the last patient you cared for, what would a new or worsening infection look like clinically? Would you see increased sputum production or wound drainage?” ED staff suggested changing this question to “Do you suspect this patient has a new or worsening infection?” Nurses also were challenged to determine if this was a new change, so we provided a look-back timeframe of 6 hours as a reference.

As previously described, after we identified challenges in drawing blood cultures within the suggested period, we developed a blood culture algorithm that includes a timeline and escalation options. This contributed to a reduced median time for obtaining cultures in ICU patients with severe sepsis.

In an effort to prevent alert fatigue and optimize the impact of early sepsis detection, nurses and other providers gave feedback to help us determine how the alerts were acknowledged and what lockout timeframes were safe. Behind-the-scenes work on physician, pharmacist, and nursing alerts and how they interacted after one clinician interfaced with an alert involved significant fine-tuning to ensure appropriate communication among team members. We stressed the importance of maintaining clinical assessment for sepsis and notification of concerns based on that assessment, rather than relying on the alert system alone. We also emphasized that the electronic alert is an adjunctive tool, not a replacement for critical thinking. (See Process and outcome monitoring by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Facilitating factors

The system changes we implemented to promote sepsis screening and timely management were crucial to improving patient outcomes. To promote early sepsis detection, we developed a protocol that allows the nurse to order and draw a blood lactate sample based on a patient’s presentation of SIRS and the nurse’s assessment of a suspected new or worsening infection. Protocol training included the rationale and procedure for sending blood samples to the laboratory for rapid analysis and developing a critical value at or above which the laboratory would contact the nurse. This allows nurses caring for patients with suspected severe sepsis to gather more data in a timely manner and to contact the provider with more comprehensive data to guide the next interventions. Also, our pharmacists developed a reference to guide the ordering of first-dose broad-spectrum antibiotics to promote appropriate pathogen coverage. These medications were added to the floor stock of all medication stations on all units.

RRT nurses and respiratory therapists

UCSFMC nurses can call on respiratory therapists and RRT nurses when they suspect sepsis. The latter provide ongoing education to unit nurses and other providers on the medical and surgical teams regarding early signs of new and worsening sepsis and appropriate interventions. Most important, they serve as a resource for unit nurses, who already are multitasking and may have other patients to care for. They expedite the process of obtaining laboratory samples, cultures, I.V. access, and reducing barriers to timely administration of antibiotics, fluids, and vasopressors.

Moving forward

At UCSFMC, plans for continuous process improvement include:

- optimizing and implementing the electronic sepsis surveillance program throughout all inpatient units

- developing a dashboard that displays outcomes of our sepsis initiative

- continually identifying opportunities for improving the care of sepsis patients by engaging with frontline clinicians, patients, and families.

We’ve learned that the keys to success in improving patient outcomes include use of a systems approach by the collaborative interdisciplinary team to engage frontline clinicians, evaluate workflow impacts, and promote the shared goal of improving care in the effort to reduce the burden of sepsis on patients, families, and the healthcare system.

Selected references

Aitken LM, Williams G, Harvey M, et al. Nursing considerations to complement the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(7):1800-18.

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580-637.

Kleinpell R, Schorr CA. Targeting sepsis as a performance improvement metric: role of the nurse. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2014;25(2):179-86.

Levy MM, Artigas A, Phillips GS, et al. Outcomes of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign in intensive care units in the USA and Europe: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(12):919-24.

Schorr CA, Zanotti S, Dellinger RP. Severe sepsis and septic shock: management and performance improvement. Virulence. 2014;5(1):190-9.

The ProCESS investigators. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. New Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1683-93.

The authors work at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center. Hildy Schell-Chaple is a clinical nurse specialist in adult critical care and an associate clinical professor in the department of physiological nursing at the School of Nursing. Melissa Lee is a clinical nurse specialist in adult acute care.

Note: All names in scenarios are fictitious.

1 Comment.

This article was very informative on Sepsis management and

giving clear direction in the role of nursing care.