“What do you see in his eyes?” asks Dr. Rothenberg. After a brief pause, someone replies, “He looks sad.” Another states, “He’s kind of emaciated.” After directing us to look just below the left eyelid, Dr. Rothenberg asks, “Do you see a sign of a scar?” Several of us nod. She tells us this scar is a remnant of trachoma, also called Egyptian ophthalmia.

This clinical scrutiny is taking place not at the bedside of a teaching hospital but in the Egyptian gallery of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Dr. Rothenberg, a retired pathologist and now a museum docent, is our guide. When I’d requested a student group tour called “Health and Illness in Art,”

I first was told the museum had no themed tours—but then it created one for us and we’ve been back three times. During the tour, nursing students examine great art while honing their observational skills.

For centuries, art has depicted various states of health and illness. As we examine the Metropolitan’s masterpieces, we reflect not only on the history but also the health of the figures represented. Our guide shows us a Rembrandt painting of a man with syphilis. She instructs us to examine the buboes of Saint Roch depicted in a stained glass from the Middle Ages. We marvel at the dignity portrayed in the Death of Socrates, a painting by Jacques-Louis David. In Renoir’s late works, we see how his debilitating arthritis transformed his work. In front of Fernando Botero’s paintings, we smile shyly at his subjects’ unapologetic obesity. A sarcophagus of a Roman physician engraved with the trappings of his profession reveals that even thousands of years ago, advertising and self-promotion didn’t end at death’s door. We see artworks that confirm our guide’s observation at the beginning of the tour—that nothing truly is original and human nature hasn’t changed much over the millennia.

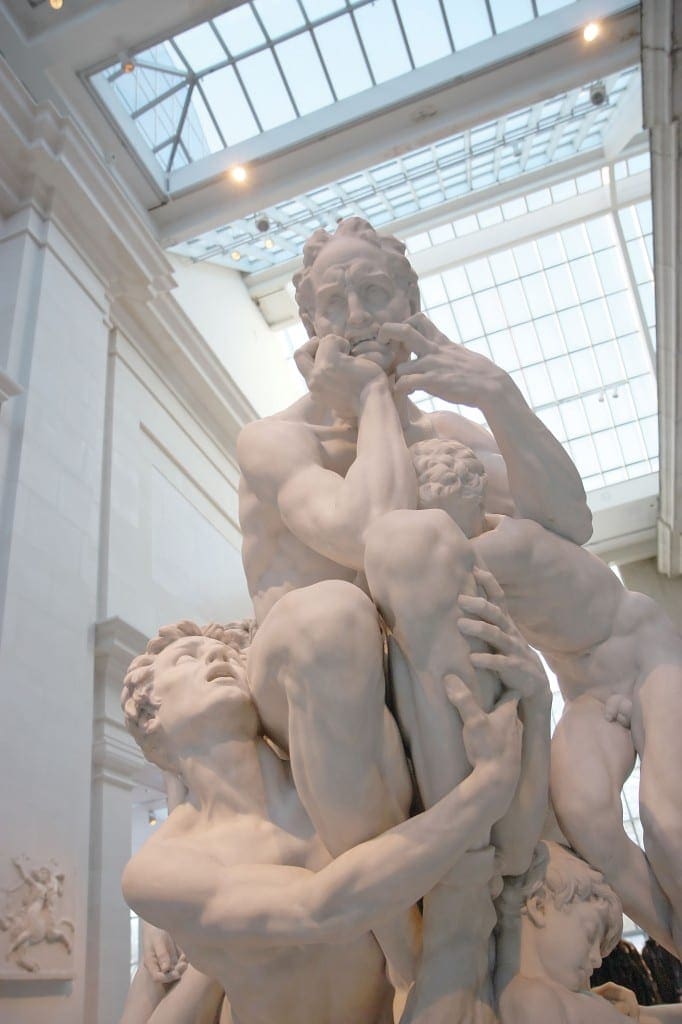

My personal favorite is the sculpture of Ugolino and his sons by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (at left). Ugolino was accused of treason and sentenced to die of starvation with his sons, all of them locked in a tower. Here we stand and stare at the prisoners’ nakedness, seeing the despair and terror in the sons’ eyes as they offer themselves as food for their starving father. We see the tension in their muscles and bones, and imagine the cries that might have emerged from their lips. Heavy chains at the sculpture’s base punctuate the subjects’ inescapable destiny—death. The sons’ sacrificial offer makes me think of the enormous self-denial families endure for their sick loved ones. In Ugolino’s contorted pose, I see stress—the consequence of many illnesses—immortalized in marble. The subjects’ imprisonment calls to mind the poor health suffered by many among our incarcerated population. Their sentence of starvation brings to mind diabetes at a cellular level (with cells starving amidst plenty), as well as the mountain of food that goes to waste in hospitals—and elsewhere—every day. The subjects’ nakedness reminds me of the loss of dignity some patients suffer from the carelessness of healthcare workers who fail to ensure their privacy.

Nurses are living witnesses and recorders of life as it occurs in real time, at the bedside and elsewhere. Although few of us take brush to canvas to document our patients’ appearance or the dramas they live out every day, we are masters nonetheless—not in the sense of Rembrandt or Picasso but in the purposeful rendering and application of the healing arts. In some ways, perhaps, we’re in the same league as the great artists.

Last month during clinicals, the patient of one of my students died. On his bed someone had carefully arranged objects of apparent importance to him—stone quartz, a bracelet, a stick with a hollowed gourd attached to it. As we gathered around the bedside, I asked everyone to look carefully and remember where each object was placed, reminding them that after postmortem care, we’d have to put these back where we found them. During this time, our movements were gentle and focused out of reverence for the patient, akin to those of a painter or a sculptor. The room was as quiet as an artist’s studio. Perhaps nurses are artists. Or maybe we’re the subjects of a master creator of a higher order, whose palette is the world.

Our museum visits are akin to walking rounds at the hospital—rounds that enable us not just to see the triumph of artistry over the mundane and the monotonous, but to sharpen our assessment skills. The visits have initiated tiny ripples in the reflecting pool of the observer’s mind. Observation is the requisite for masterful reflection and clinical precision. Yet an irony of nursing education is its reverence for critical thinking at the expense (too often) of observation. Observing art is a sublime exercise in truly looking and feeling—one that can help us become better nurses.

Fidelindo Lim is a clinical faculty member at New York University College of Nursing and a nurse educator at New York Downtown Hospital in New York City.