Neurocysticercosis, the most common parasitical infection of the central nervous system, is caused by accidental ingestion of eggs from Taenia solium (pork tapeworm). This potentially fatal infection is the most widespread cause of acquired epilepsy in developing countries.

Neurocysticercosis is a major public health concern in developing countries and is emerging in the United States and other industrialized nations, often as a result of immigration of people with the disease. (See Incidence of neurocysticercosis.) The infection is preventable, but little is being done to prevent, monitor, or diagnose it. This makes it critical that nurses and other healthcare providers become familiar with the disease and recognize those at risk.

| Incidence of neurocysticercosis

About 2.5 million people worldwide carry the adult tapeworm, and many more are infected with cysticerci (cysts or larvae from the tapeworm) Neurocysticercosis is endemic in Mexico, Central and South America, sub-Saharan Africa, Indian subcontinent, Indonesia, and China. In some of these endemic regions, the incidence can reach up to 3.6%. In the United States, neurocysticercosis is mainly a disease of immigrants. It’s most prevalent in California, Texas, and New Mexico. According to one recent study, an estimated 1,000 new cases require hospitalization every year. Neurocysticercosis creates a large economic burden because a hospital stay can total an average of $37,600, with Medicaid being the most common insurance payer for patients who have the disease. |

Cause and transmission

Neurocysticercosis is transmitted via fecal-oral contact with carriers of the adult tapeworm. It can spread to unaffected people by consumption of food that has been contaminated by people infected with the parasite, improper hand washing, or improper handling/cooking of food.

The Taenia solium parasite has a biological life cycle that includes two common hosts, humans and pigs. The human is the definitive host and carries the intestinal tapeworm, while the pig is an intermediate host and carries the cysticerci.

The parasite has a scolex (head) that has a double crown of hooks/suckers, an unsegmented neck, and a large body with several hundred proglottids (reproductive system). When the host ingests tainted food or feces containing parasitic eggs, they evaginate (attach) to the small intestine with their suckers and hooks, and then develop strobila (chains of proglottids).

One proglottid can contain up to 60,000 eggs. These eggs then are excreted in the feces of the host, pigs ingest the tainted feces or humans ingest tainted food, and the life cycle is repeated. The eggs also can cross into the bloodstream. They are then transported to tissues, most commonly the central nervous system, where they reside as cysticerci.

Cysticerci develop over a period of 3 to 8 weeks after ingestion and can form in different sites. During this initial “viable or active” phase, the cysticerci don’t cause inflammation and patients are asymptomatic because of taeniaestatin (a parasite serine proteinase inhibitor). Taeniaestatin interferes with lymphocyte and macrophage function, which can inhibit the body’s normal immune response to the parasite. Cysticerci can remain in this stage for many years.

Symptoms

Patients can be simultaneously infected with active (viable) and inactive (calcified) cysts or cysticerci. Eventually, host immune and inflammatory cells attack the cysts to kill and break them down. This can cause edema, neurological symptoms, and seizures. The lesions then either resolve or form calcified granulomas.

Neurocysticercosis usually peaks 3 to 5 years after infection, but has been reported to have symptomatic onset more than 30 years after infection. Clinical manifestations of the infection depend on the size, location, and number of cysts along with degree of inflammatory response.

Cysts can be located in the brain parenchyma, extraparenchymal tissues, or both. Parenchymal cysts are associated with headache and seizures. Extraparenchymal cysts cause elevated intracranial pressure, such as headache, nausea, vomiting, and altered mental status.

Parenchymal cysts are the most common form of cysts present in patients with neurocysticercosis, accounting for more than 60% of cases, which explains why seizures are the most common clinical manifestation.

Many cysts in the brain parenchyma and an intense immune response can cause diffuse edema in the brain that resembles encephalitis. Symptoms include fever, seizures, headache, nausea, vomiting, change in level of consciousness, and visual disturbances.

Treatment and follow up

Treatment of neurocysticercosis depends on the number of cysts, stage of cyst (active versus inactive), and degree of cerebral inflammation. Patients who are asymptomatic with inactive (calcified) cysts don’t usually need treatment. Patients who are symptomatic with active or inactive cysts may need treatment with a combination of surgery, antiseizure, antiparasitic, and/or corticosteroid medications.

Antiparasitic regimens last from days to weeks to months. Antiseizure medications may be needed 6 to 12 months after resolution of cysts.

Hospitalization and close monitoring is required for the first week of antiparasitic therapy because of possible rapid clinical deterioration. Patients should follow up with infectious disease and neurology/neurosurgery specialists after discharge. Repeat radiographic imaging should be performed to monitor for resolution of cysts and development of calcifications.

Patients with one active cyst have a better prognosis than patients with multiple viable cysts.

Case study

Joseph Garcia*, a 32-year-old Hispanic male, came to the emergency department (ED) and reported a month-long history of headache. He was initially prescribed analgesics and discharged home. Mr. Garcia returned to the ED a few days later for dizziness and severe headaches. The headaches were becoming more frequent, occurring multiple times daily, and lasting for hours at a time.

Mr. Garcia had a history of nausea that accompanied the headaches but denied vomiting, visual obscurations, diplopia, focal motor or sensory symptoms, gait issues, and incontinence. He was alert and orientated and had no history of seizures or change in level of consciousness. He had no medical history and took no medications or over-the-counter products. Social history was significant for migration from Mexico 11 years ago. He currently worked on a dairy farm.

Examination was positive for horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus (an involuntary movement or beating of the eye when assessing horizontal or vertical gaze). All other review of systems and physical exam were negative.

Diagnosis

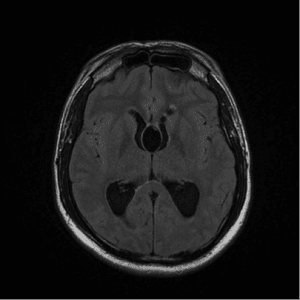

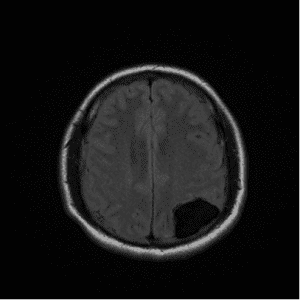

A CT of the brain revealed hydrocephalus and multiple cystic lesions as well as calcified lesions consistent with neurocysticercosis. An MRI of the brain revealed eight lesions, some in colloid and other in granular-nodular stages. (See MRI images of neurocysticercosis.)

On the basis of signs, symptoms, and imaging results, Mr. Garcia’s headaches were attributed to obstructive hydrocephalus caused by parenchymal neurocysticercosis, and he was admitted to the neuro critical care unit (NCCU).

Intervention

The NCCU nurses monitored Mr. Garcia closely for 10 days. Monitoring included hourly neurological checks to assess for worsening hydrocephalus. Key components of the checks were assessing for headache, nausea, vomiting, altered mental status/change in level of consciousness, and focal neurologic deficits such as numbness, tingling, weakness, and ataxia.

The nurses also monitored Mr. Garcia for decreased visual acuity associated with papilledema and extra ocular movements. A sign of worsening hydrocephalus is vertical gaze palsy, the inability to gaze upward or downward when asked.

The head of Mr. Garcia’s bed was elevated greater than 45 degrees and blood pressure was monitored with the goal of keeping him normotensive (< 160 systolic mmHg).

Mr. Garcia received medications for nausea (ondansetron) and pain control (acetaminophen). Narcotics were avoided because of the risk for increasing intracranial pressure. Corticosteroids (dexamethasone) were initiated to decrease cerebral edema from inflammation caused by resolving (dying) cysts.

Antiepileptics were not used because there was no history or presentation consistent with seizures. Antiparasitic medications (albendazole) were not initiated until after surgery. These medications can weaken the cyst membrane, causing friability and/or adherence to the ventricular wall.

Surgery

Mr. Garcia underwent stereotactic assisted right frontal transcortical resection of the foramen of Monro cyst with a right ventriculostomy. An external ventricular drain was placed during surgery for cerebrospinal fluid output.

Nurses monitored intracranial pressure postoperatively in case it increased to more than 20 mmHg. They also watched for hydrocephalus, acute encephalitis, meningitis, and infection of the drain.

Outcome

The external ventricular drain was successfully weaned and removed without complications. Mr. Garcia’s surgical incision remained clean, dry, and intact. No new neurological symptoms developed, and the headaches resolved before discharge.

Mr. Garcia was discharged on albendazole to treat the parasite and acetazolamide to decrease swelling and prevent seizures. He was instructed to taper his steroids over 28 days. Mr. Garcia was followed as an outpatient in the infectious disease clinic and neurology/neurosurgery clinic. He recovered well with no new symptoms.

Nursing implications

Nurses play a key role in the care of patients with neurocysticercosis. Performing thorough and accurate neurological checks and recognizing changes from previous assessments is critical, as is providing patient education.

Education includes stressing the importance of proper hand washing, sanitary practices, and food handling and preparation. Emphasizing medication compliance is vital, because these patients may need long-term treatment with antiparasitic and antiepileptic drugs. Other essential points include seizure education, such as driving or activity restrictions, and the need for ongoing follow-up after discharge.

Selected references

CDC. Neglected Parasitic Infections in the United States: Neurocysticercosis. 2014. www.cdc.gov/parasites/resources/pdf/npi_cysticercosis.pdf

Chandran S, Balakrishnan R, Umakanthan K, et al. Neurocysticercosis presenting as isolated wall-eyed monocular internuclear opthalmoplegia with contraversive ocular tilt reaction. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3(1):84-8.

Del Brutto OH, Rajshekharm V, White AC, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology 2001; 57:177. Lippincott Williams &Wilkins. Accessed July 14, 2014. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-cysticercosis?source=search_result&search=neurocysticercosis&selectedTitle=1%7E15, 7/16/2012

Rajshekhar V. Surgical management of neurocysticercosis. Int J Surg. 2010;8(2):100-4.

Zafar M. Neurocysticercosis. 2013. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1168656-overview

*Patient name is fictitious.

Maranda C. Gary is a certified family nurse practitioner in the neuro critical care and neuro vascular units at Bronson Methodist Hospital in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

2 Comments.

You have shared informative article here ! Great information…….

Does nicotine interfere in the treatment of nueroCysticercosis?