THIS IS WHERE we share some of the comments, insights, and thoughts we receive from readers. Contact us at myamericannurse.com/send-letter-editor.

Nurse suicide

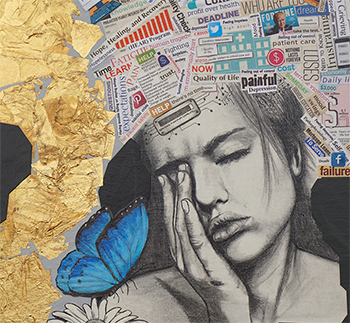

I would like to thank Leah Heather Rizzo for bringing [the topic of nurse suicide] to the forefront (myamericannurse.com/suicide-among-nurses-might-hurt-us/). I have also suspected that nurse suicide is underreported, unrecorded, and much more common than we would like to believe. I also have tried to find nurse suicide statistics and queried government datasets and death records in Can a da while I was a graduate student to no avail. Nurses face unprecedented violence at work, increasing workload, bullying, and unmeasurable stress to care for others, all the while depleting their own stores of self-preservation and self-care. How could nurses not have an increased incidence of suicide and mental health issues? Articles like this will help decrease stigma and open the door to conversations that are long overdue. In the meantime, nurses in the United States and Canada need to gather their statistics on nurse suicide in order to lobby for workplace mental health recognition, improve access to resources, and help our fellow nurses who suffer in silent hopelessness.

I would like to thank Leah Heather Rizzo for bringing [the topic of nurse suicide] to the forefront (myamericannurse.com/suicide-among-nurses-might-hurt-us/). I have also suspected that nurse suicide is underreported, unrecorded, and much more common than we would like to believe. I also have tried to find nurse suicide statistics and queried government datasets and death records in Can a da while I was a graduate student to no avail. Nurses face unprecedented violence at work, increasing workload, bullying, and unmeasurable stress to care for others, all the while depleting their own stores of self-preservation and self-care. How could nurses not have an increased incidence of suicide and mental health issues? Articles like this will help decrease stigma and open the door to conversations that are long overdue. In the meantime, nurses in the United States and Canada need to gather their statistics on nurse suicide in order to lobby for workplace mental health recognition, improve access to resources, and help our fellow nurses who suffer in silent hopelessness.

— Patricia Dekeseredy, MScN, RN Morgantown, WV

The October 2018 CNE article “Suicide among nurses: What we don’t know might hurt us” is timely and illuminates a tragic occurrence found in the nursing profession. While the actual number of suicides committed by nurses in the United States is conflicted and outdated, the data reveals that in 2016, suicide was the 10th leading cause of death for people age 10 years and older. Just recently our hospital lost a talented and caring young nurse. She, for reasons unknown, chose to take her own life. Devasted coworkers racked their minds trying to piece together what clues might have been available, and what actions could have been taken to prevent the loss of a beautiful human being. Very often, it’s the one who provides a healing touch who desperately needs the very same help.

This article highlights a variety of factors which can lead to suicide and offers prevention strategies. There are interpersonal factors, along with workplace stressors such as burnout and feelings of job detachment, that can be addressed by the nursing profession. We need to be proactive to provide a workplace that is conducive to a supportive and affirming environment not just for the work at hand, but for those who do it. Taking action to develop and promote a national standard for the prevention of nurse suicides is a must, and the workplace is a good place to start.

— Cathy Magallanez, MSN, RN, PCCN Quinton, Virginia

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide rates rising across the U.S. June 7, 2018. cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0607-suicide-prevention.html

Davidson JE, Stuck AR, Zisook S, Proudfoot J. Testing a strategy to identify incidence of nurse suicide in the United States. J Nurs Adm. 2018; 48(5):259-65.

Family presence during resuscitation

I am writing in response to the article entitled “Family presence during resuscitation in the intensive care unit” by Carolyn Bradley, Janet Parkosewich and Bertie Chuong (myamericannurse.com/family-presence-resuscitation-icu/). As a recent associate degree in nursing graduate and a first year neurosurgical ICU nurse, I found this article extremely informative regarding the process of initiating family presence during resuscitation (FPDR) and how to become a change agent early in my career. FPDR is a controversial issue, not only for family members during these resuscitations, but also for the interdisciplinary staff assisting in the decision and process. This article accurately emphasizes the benefits of FPDR including reduction in family member’s anxiety, minimizing feelings of patient abandonment, and the comfort provided knowing all efforts have been made to revive their loved ones. As noted by the authors, there are many driving and restraining forces that will either obstruct this change or expedite the outcome of implementation and success. One of the greatest hurdles initiating FPDR in an organization is changing the status quo and solidifying this policy into a unit’s culture. In my organization, FPDR is in our policy; however, I have found that lack of education provided to staff can be one of the largest barriers in implementing FPDR effectively on our unit.

Kurt Lewin’s 3-step change model as explained in this article includes a step-by-step breakdown of how this can be implemented into an organization. One of the key pieces of information discussed is assembling an FPDR steering committee. This would need to be composed of a multidisciplinary team that views FPDR as a benefit in patient-centered care. The controversy lies with the amount of education provided by an organization to promote this policy. It is interesting that as critical care nurses we are expected to promote and effectively implement FPDR on our unit, yet I have not been provided with any formal or informal education regarding why this policy exists in our organization. I’ve been in a classroom and clinical setting for the past 6 months as a new graduate critical care nurse and have learned abundant amounts of information regarding critical care and nursing. I am surprised that I have yet to be exposed or educated on this policy, especially since resuscitation is a common occurrence on all critical care units.

In an article entitled “Family presence during resuscitation: Impact of online learning on nurses’ perception and self-confidence” published in July of 2016 in the American Journal of Critical Care, Powers and Candela performed a study that shows online learning is an effective tool when educating nurses on FPDR. One statistic that was astonishing in this study is out of the 72 critical care nurses in their sample size, only 29.7% worked in a facility or unit that had an FPDR policy and 41.9% actually had received any prior education on FPDR. One recommendation mentioned and could be very useful in implementing this education would be to add FPDR online learning in current ACLS certification renewal courses, which increases its exposure to a majority of resuscitative care providers.

In conclusion, the authors provided a great resource of information on how to educate staff and implement FPDR policy in an organization. Although this policy has already been implemented in my unit, I find it to be less than effective as there is much room for improvement. After reading this article, I was inspired to center my critical care residency project and unit in-service on the lack of education that is provided by our healthcare system regarding FPDR. I believe that there is room to explore this topic and policy in my department while becoming the driving force to educate our unit as to why we are performing FPDR and how to perform it effectively. By utilizing the information provided in this article, I plan on being the change that will allow my organization to share a common vision in providing effective efforts in FPDR.

— Jamie Dupont, RN

Journaling

In reading my November issue of American Nurse Today I found an article on journaling (myamericannurse.com/journaling-valuable-registered-nurses). While attending a workshop given by a nurse-attorney we were told never to journal anything about our job as this can be “discoverable” in any future litigation. The article in this issue promotes journaling about work experiences. I wonder what the response would be from a nurse-attorney on this practice. Is there one on staff of this publication who could comment?

— Paula Milner MS, RN Phoenix, AZ

American Nurse Today reached out to a nurse-attorney who has contributed to the journal. Here are her comments:

I think journaling is a very useful tool— as long as it does not include actual descriptions of actual events with actual patients. Keep in mind that journaling about adverse events poses a potential risk to nurses. In a deposition, nurses will be asked if they have any logs, journals, or diaries and if so, they can be discoverable and will need to be produced. There will always be something in that journal that can be a statement against that nurse’s interest. Additionally, nurses will be asked if they keep this kind of detailed log on every patient they take care of. The answer is no, so the next obvious question is why they did so in this case. It is difficult to overcome presumption that the reason the nurse made a detailed log in this case is because something happened that should not have. It also makes the nurse less credible when under oath he or she testifies to not remembering some details about the case when being asked about it in what can be years after the event. There are also potential problems with HIPAA, state privacy laws, violation of organizational policies, and professional misconduct charges. I always advise nurses to NOT keep journals, logs, or diaries about patient events, much less copies of documents like incident reports or medical records for just these reasons. Journaling about feelings and one’s personal journeys can be helpful. Just remember that journaling about feelings is one thing—memorializing adverse events is another.

— Edie Brous, Esq. PC Nurse Attorney

Note: This information is not intended to provide legal counsel.

ant12-Reader Feedback-1206