To honor National Alzheimer’s Disease Awareness Month, I would like to highlight a feature of the disease that’s of special interest to me as a linguist: language function.

As someone obsessed with language and language’s connection to neurology, I’m interested in the effects Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has on patients’ language function. I was able to learn about this connection from an expert during my time working in the aphasia research and rehabilitation lab at Temple, and I would like to share my experiences with you.

The lab I worked in was adjacent to another lab which was actively investigating novel therapies in language function for patients with progressive aphasia and dementia. Dr. Jamie Reilly was the primary investigator of the lab, and although we didn’t work directly with one another, I was able to learn a lot about the linguistic aspects of AD from him.

Language impairments in patients with AD occur due to a decline in the patients’ semantic and pragmatic language processing. Another connected diagnosis is frontotemporal dementia (FTD), which is linked to semantic dementia (SD) or progressive nonfluent aphasia. SD is a type of aphasia that manifests itself as a loss of semantic memory, which is the part of our memory that allows us to recall words or concepts.

So, why is SD connected to AD and FTD? Since AD and FTD are degenerative neurologic conditions, when the disease begins to affect the part of the mind involved in semantic memory, it may cause the patient to lose his or her understanding of key lexical items (vocabulary) that would otherwise be considered commonplace.

For example, if a patient with AD or FTD isn’t able to assign the words “cat” or “dog” to the respective objects, he or she may instead use vague or related words, such as “mouse” or “animal,” which are semantically related to the correct target words but don’t convey the correct meaning. SD also can manifest itself in the inability to understand the meanings of words, difficulty understanding spoken language, and problems with reading and writing.

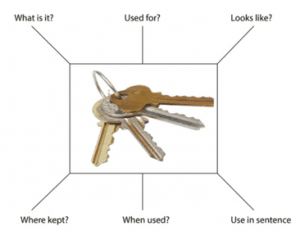

Similar to the aphasia lab I worked in, Dr. Reilly’s research focused on training participants’ semantic memories through a core list of vocabulary. Patients were provided a visual illustration (see below) of each lexical item and were prompted to describe various semantic features of the item. Then, the patient would use the word in a novel sentence.

(Source: Reilly-Coglab.com)

AD is an extremely impactful diagnosis not only for the patient, but for the caregivers as well. Watching your loved ones battle this disease is hard enough, but watching a decline in their communication abilities can add even more stress on all parties involved.

Please find more resources on FTD here, and more about Dr. Reilly’s lab here.