“This patient has been stuck four times. Can you help me start her I.V.?”

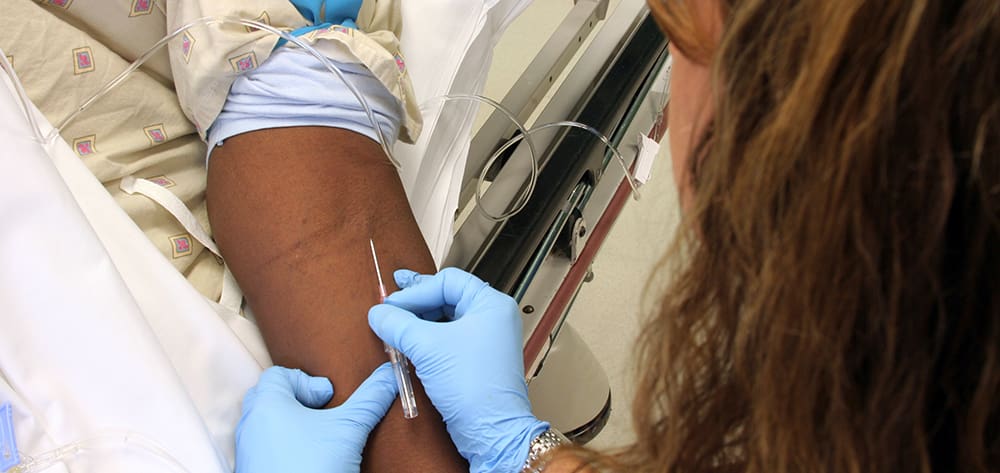

How do you feel when a colleague asks you to help in this situation? Sometimes, obtaining peripheral I.V. access is challenging even for experienced clinicians. Common techniques for making vessels more visible and distended for I.V. insertion include use of heat, illumination devices, or a tourniquet while the extremity dangles, as well as rubbing the skin over the vein.

But what happens when these methods fail? In some cases, patients have to undergo multiple insertion attempts or end up with a central line. But those results can be avoided when ultrasound is used to obtain peripheral I.V. access. Called ultrasound-guided peripheral I.V. (USGPIV) placement, this technique reduces the number of unsuccessful attempts and ensures catheter visualization in the vessel. It can eliminate delays and frustration, and ultimately reduces the use of supplies and staff time.

Adopted by many emergency departments, USGPIV can be used in many care settings. USGPIV originated with PICC and vascular clinicians and spread to EDs across the country (mainly because all EDs are required to have ultrasound equipment). It quickly became a useful tool in obtaining vascular access. Although USGPIV insertion may take longer than traditional I.V. line insertion, it’s often faster than multiple failed traditional insertion attempts. Although it requires enhanced insertion skill, it is more cost-effective than central venous access and a good alternative when central access isn’t needed. A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placed by a vascular-access nurse can cost up to $450. USGPIV line placement costs only about $45 and is a much better value when central access isn’t necessary.

When a clinician skilled in USGPIV is available, the technique can be used effectively in emergency situations where immediate venous access is needed. The time needed for USGPIV insertion may vary widely, depending on clinician skill. For patients who need immediate access, other access routes may have to be considered.

This clinical practice guideline describes USGPIV to help introduce the technique to clinicians in a wide variety of healthcare settings. The guideline was developed by nursing staff from three Magnet®-designated hospitals in the Duke University Health System in North Carolina, representing emergency care, critical care, and vascular-access nursing specialties.

Benefits and risks

Theoretically, USGPIV can be done in patients of all ages. It’s especially useful for visualizing vessels in:

- obese patients

- edematous or hypovolemic patients whose veins aren’t readily visible on the surface

- those with vein-debilitating conditions, such as sickle cell disease or cancer

- those who’ve undergone repeated venipuncture to administer prescription drugs or illegal substances to manage chronic conditions.

USGPIV can be used in any patient-care setting where nurses are competent in the technique and have access to ultrasound equipment. Ultrasound equipment can range from a high of $30,000 for a multipurpose unit, to $15,000 for vascular visualization only, to a low of $4,500 for newer devices designed for USGPIV insertion only.

Patient satisfaction

Duke’s patient- and family-centered care philosophy drives our practice of limiting failed venipuncture attempts and providing a service that patients with previous positive USGPIV experiences can request. Duke staff members appreciate the benefits to patients. And rather than having to contribute to continued I.V. insertion attempts with uncertain outcomes, they can request the expertise of colleagues. Patient satisfaction improves when fewer failed attempts are made, treatment begins sooner, and central venous access is avoided in nonemergency situations. We encourage family members to observe the procedure to help them understand vessel physiology and the factors that can make I.V. access harder to obtain.

Contraindications

Like traditionally inserted peripheral I.V. lines, USGPIV lines aren’t appropriate for extremities with torn or burned skin, arteriovenous fistulas, deep vein thrombosis, veins deeper than 1.5 cm, post-mastectomy patients who’ve undergone lymph-node dissection, or patients who will need I.V. access for more than 6 days. In these cases, clinicians should consider a longer-term access device, such as a midline catheter or a PICC. Also, special skills are needed to use USGPIV lines for pediatric and neonatal procedures.

Who performs the procedure

Although sonography requires additional dexterity, any clinician who can insert a peripheral I.V. line is a candidate for learning the USGPIV competency. To gain competency, clinicians must obtain appropriate didactic and hands-on simulation training in the classroom, along with supervised insertions. Completing the traditionally placed peripheral I.V. competency is a prerequisite for completing the USGPIV competency.

Components of the USGPIV competency include:

- device preparation

- infection-control measures

- patient positioning

- ability to differentiate anatomic structures on ultrasound

- aseptic technique

- correct entry angle for insertion

- confirmation of tip placement

- verification of blood return and patency to flushing

- sterile dressing

- correct documentation

- troubleshooting techniques

- patient teaching.

To make the training cost-effective, staff must use their newly learned skills. Opportunities to use these skills depend on developing supportive processes (policies and procedures and competent preceptors) within the organization.

USGPIV training

Skilled nurses teach clinicians the USGPIV technique in a 4-hour class consisting of didactic information and simulated demonstration. Core content includes anatomy and physiology, infection prevention, equipment selection, insertion technique, and patient and family education. To enroll in the class, the registered nurse must have consistent peripheral I.V. insertion experience with demonstrated proficiency and knowledge of I.V. therapy indications and complications. At this time, the skill isn’t recommended for newly licensed nurses. Confidence to support continued competence requires at least 10 successful USGPIV insertions.

Patient assessment and vein selection

To use USGPIV, clinicians should start by assessing the patient’s venous status. (See Criteria to support venous access decisions.) Success increases with appropriate vein selection, which should include evaluation of vein location and vessel confluences.

Criteria to support venous access decisionsThese criteria are based on various sources, including the 2011 Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice. 1. Peripheral access for therapy of less than 6 days: peripheral I.V. (PIV) with or without ultrasound guidance. Uses include contrast media administration for diagnostic studies. 2. Midline catheters (peripheral access devices) may be used for isotonic solutions when the patient has limited recannulation sites and short-term therapy needs. 3. Intraosseous access can be used in emergency situations when I.V. access is needed for less than 24 hours. 4. External jugular access can be used for therapies of less than 72 hours and when upper extremity peripheral sites are exhausted. 5. PIVs in the lower extremities are a last resort and should be removed as soon as more permanent access is established. Lower-extremity PIVs are contraindicated in patients with diabetes and peripheral vascular disease. 6. PICCs or nontunneled catheters can be used in the internal jugular, external jugular, subclavian, or femoral veins for short-term central access. 7. PICCs or tunneled noncuffed catheters can be used in the internal jugular or subclavian vein for central access needed for more than 6 days and up to several weeks. 8. PICCs, tunneled cuffed catheters, or implanted ports can be used for central access if needed for more than several weeks. Source: Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice. J Infus Nurs. 2011: 34(1s), s1-s108. |

When assessing veins using ultrasound, be sure to evaluate vessel health. Healthy veins appear round in the transverse view, follow the natural straight pathway up the extremity without tortuosity, compress easily when light downward pressure is applied to the transducer, and enlarge when a tourniquet is applied. Take care not to puncture a vessel that pulsates when compressed, because this signals arterial flow.

Optimally, choose a vein with a diameter at least twice (or, preferably, three times) as large as the catheter’s outer diameter. This desired catheter-to-vein ratio is based on outcomes from data on thrombus-formation risks associated with PICCs. Maintaining this ratio allows for hemodilution around the catheter and decreases thrombus-formation risk associated with stasis and vascular endothelial disruption.

Recent ultrasonography practice guidelines suggest the catheter should be greater than 1.75’’for adults. Be sure to choose a catheter long enough to prevent dislodgement, especially if you’re using a deeper vein. Patients may inadvertently twist the extremity and dislodge the catheter, unless enough of the catheter is seated in the vessel itself (and not residing mostly in subcutaneous tissue). This is especially important when using a vessel deeper than 1 cm. As with traditional I.V. insertion, once you’ve made an attempt, avoid further attempts distal to that site for 24 hours to prevent infiltration at the proximal venipuncture site.

Be aware that USGPIV lines shouldn’t routinely be placed in an area of flexion. The Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice state that any catheter placed near a flexion area should have a joint-stabilization device applied to prevent flexion-related irritation of the endothelium and infiltration.

Poor visualization of or inability to palpate a vessel suggests the need for a clinician with USGPIV expertise for the first attempt. Hand-off communication and discussion with the healthcare team about the numbers of unsuccessful attempts at peripheral I.V. line insertion are critical, allowing clinicians to consider USGPIV before other access options have been eliminated.

USGPIV procedure

USGPIV can be done successfully with or without a tourniquet, as long as the clinician remembers the vein is distended when a tourniquet is applied and is smaller once the catheter has been placed and the tourniquet is removed. Always use aseptic technique during insertion. Cover the ultrasound probe with a sterile transparent dressing and sterile gel. Otherwise, the catheter could become seeded with bacteria or other infectious agents when passing through nonsterile gel. If desired, an image can be taken through most ultrasound devices to demonstrate catheter location in the vessel lumen for documentation; this is consistent with practices for physician-placed central vascular access procedures. (See Sonogram showing the catheter in the vein.)

Sonogram showing the catheter in the veinThis sonogram shows the catheter in the center of the vessel in the longitudinal view. Note that an adequate length of catheter resides in the vessel to prevent catheter dislodgment caused by extremity movement.

Image courtesy of Duke University Health System © 2013. |

The vessel can be cannulated using either the transverse or longitudinal view. The transverse view is recommended; then the clinician should switch to the longitudinal view to confirm catheter placement. In both views, the clinician should visualize the catheter tip both during and after line insertion to confirm proper tip placement. During the entire procedure, be sure to identify and visualize the catheter tip to promote successful cannulation and maintain correct catheter position within the vessel lumen.

One clinician with developed dexterity can accomplish line insertion. Dexterity depends on probe size, how well the probe fits the hand, and consistent use of the same equipment. A two-person technique allows for additional hands to retract the skin, with one clinician focusing on needle placement and the other on manipulating the probe. To keep the skin taut, it helps to have someone provide comfort to a pediatric patient or other patient who might move around too much.

Complications

USGPIV complications resemble those of traditionally placed PIV catheters. Complication risks increase as vessel depth increases. Use of vessels deeper than 1.5 cm isn’t recommended; consider alternative means of access for these veins.

Measuring outcomes

To identify measurable outcomes and determine the success of a facility’s USGPIV program, line survivability ideally should be the same as for traditional peripheral I.V. lines. The same potential complications of peripheral line insertion and maintenance—infection, inflammation, phlebitis, extravasation, and infiltration—should be tracked. Details of serious insertion-related complications, such as nerve irritation, hematoma formation, and arterial puncture, should be documented in the occurrence reporting system and reported to the provider and program leadership. Patient comfort and satisfaction with the procedure can serve as indicators of program success.

Promoting a practice change

To promote use of USGPIV in your facility, practitioners from each discipline should query their licensure board regarding scope-of-practice implications. In many states, USGPIV is a facility-based competency focused on ultrasound use for vessel visualization; the technique can’t be used for diagnostic purposes.

Additional inquiry is needed to determine if nurses can perform the modified Seldinger technique (MST), an advanced skill involving catheter placement over a guidewire. MST has been used to insert traditional peripheral I.V. lines; recently, several new devices that incorporate this technique have come to market.

In light of the Affordable Care Act and lack of reimbursable charges for some procedures, healthcare providers must use the best techniques and technologies available to eliminate unnecessary use of supplies and staff time. USGPIV enhances visualization of potential I.V. access sites and helps prevent delays that arise from consulting specialized clinicians.

The authors work at Duke University Health System. Phillip Stone is a staff nurse in the emergency department at Duke University Hospital in Durham, North Carolina; Julia Aucoin is a nurse research scientist for Duke University Health System; Britt Meyer is nurse manager of the vascular access team at Duke University Hospital; Nancy Smith is a staff nurse at Duke Regional Hospital in Durham, North Carolina in the vascular access team. Sherry Nelles is a clinical practice council co-chair; Ann White is a clinical nurse specialist in the emergency department; and Jana Grissom is a staff nurse in the neuro-intensive care department at Duke University Hospital. Richard Raynor is a staff nurse at Duke Raleigh Hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Selected references

American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. AIUM Practice Guideline for Use of Ultrasound to Guide Vascular Access Procedures. White Paper; 2012. www.aium.org/resources/guidelines/usgva.pdf?. Accessed July 21, 2013.

Bauman M, Braude D, Crandall C. Ultrasound-guidance vs. standard technique in difficult vascular access patients by ED technicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(2):135-40.

Constantino TG, Parikh AK, Satz WA, et al. Ultrasonography-guided peripheral intravenous access versus traditional approaches in patients with difficult intravenous access. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(5):456-61.

Dargin JM, Rebholz CM, Lowenstein RA, et al. Ultrasonography-guided peripheral intravenous catheter survival in ED patients with difficult access. Am J Emerg Med

. 2010;28(1);1-7.

Doniger SJ, Ishimine P, Fox JC, et al. Randomized control trial of ultrasound-guided periperal intravenous catheter placement versus traditional techniques in difficult-access pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(4);154-9.

Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice. J Infus Nurs. 2011;34(1s):s1-s108.

Masoorli S. Nerve injuries related to vascular access insertion and assessment. J Infus Nurs. 2007;30(6):346-50.

Meyer BM. Managing peripherally inserted central catheter thrombosis risk: a guide for clinical best practice. JAVA. 2011;16(3):144-7.

Milling T, Holden C, Melniker L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of single-operator vs. two-operator ultrasound guidance for internal jugular central venous cannulation. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(3):245-7.

Moureau N, King K. Advanced Ultrasound Assessment for PICC Placement. PICC Excellence, Inc.; 2008. www.piccexcellence.com/picciv-education/ultrasound-training/online-advanced-ultrasound-training/. Accessed July 21, 2013.

O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39 (4 Suppl 1):S1-34.

Panebianco NL, Fredette JM, Szyld, et al. What you see (sonographically) is what you get: vein and patient characteristics associated with successful ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous placement in patients with difficult access. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(12);1298-1303.

Roszell S, Jones C. Intravenous administration issues: a comparison of intravenous insertions and complications in vancomycin versus other antibiotics. J Infus Nurs. 2010;33(2):112-8.

White A, Lopez F, Stone P. Developing and sustaining an Ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous access program for emergency nurses. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2010:32(2):173-88.

Witting MD, Schenkle SM, Lawner BJ, et al. Effects of vein width and depth on ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous success rates. J Emerg Med. 2010;39(1):70-5.

4 Comments.

I have been a pin cushion since the age of 2 while a research patient at Johns Hopkins. (I’m 54 now.) to say my veins are shot is an ubderstatement. It takes no less than 5 sticks to get an iv. After reading this, my next extended visit will definitively definitely be the first procedure I receive!

We have dedicated rapid response team at my institution. The rapid response nurses are often to called to start “difficult” IV’s. All of us have taken the class to start ultrasound placed PIV’s. Some patients are asking for the service when they are admitted through the ED. It seems that more and more patients are “hard sticks”. I predict that the skill will be expected, not only from patients, but that physicians and administrators demand a group of nurses have the skill. Compensate them.

Great article! I work 3-11 and often have to insert my own IV’s.We don’t have IV team during those hours. I have more IV experience than most of the nurses on my floor. My co-workers often ask me to insert IV’s for them but I’m not an expert. The ultrasound technique would be very helpful and I will bring this up to my manager.

That is excellent to the MAX!!! How many times as a nurse I have found difficult situations. I always feel so very sorry for the patient. One must think about his/her pain and also the cost it involves. Not only monetary but also Nurse hours.