Engage patients to help prevent this possibly deadly condition.

Takeaways:

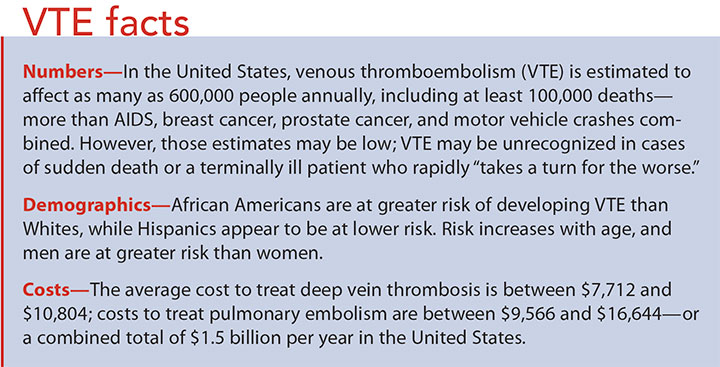

- Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is responsible for more deaths annually than AIDS, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and motor vehicle accidents combined.

- Most VTE are preventable.

- Nurses play a key role in preventing and treating VTE.

By Carolyn E. Crumley, DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, CWOCN

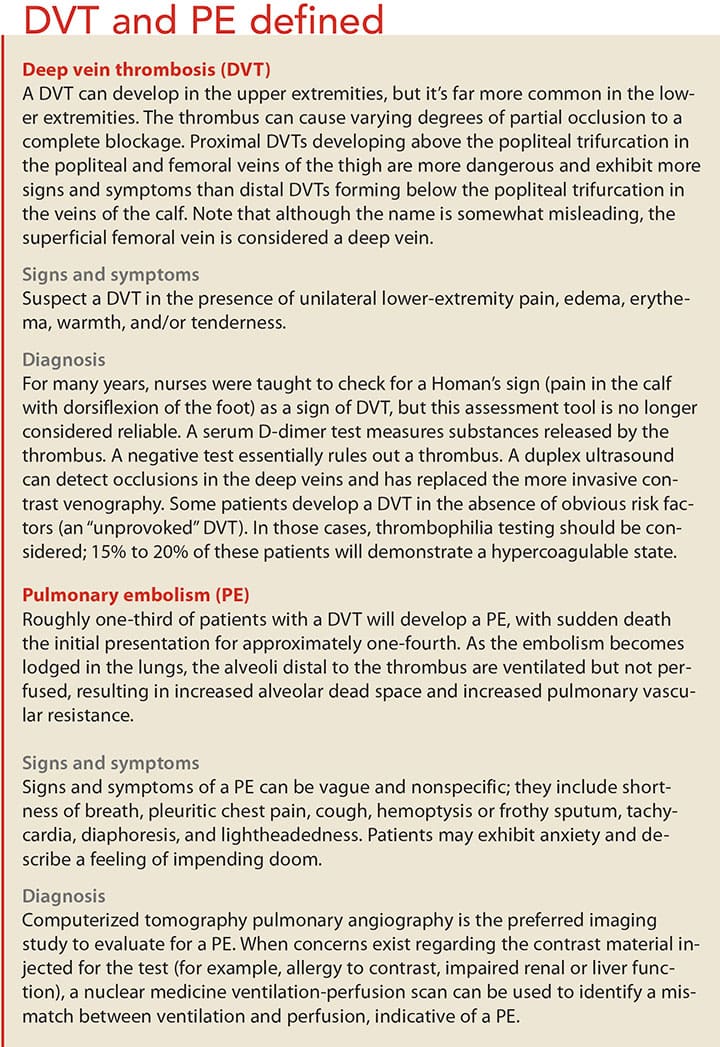

Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) is the number-one cause of preventable death in hospitalized patients. (See VTE facts.) A thrombus is a clot that forms in a blood vessel, most often in a deep vein, which results in deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The danger lies in the thrombus breaking loose from the vein and traveling through the right side of the heart to the lungs, resulting in a pulmonary embolism (PE). This process is different from a thrombus that forms in an artery and results in a myocardial infarction or cerebral vascular accident. (See DVT and PE defined.)

Beyond the immediate dangers, both DVT and PE can produce long-lasting debilitating effects. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, which develops in about 5% of individuals who survive a PE, is characterized by progressive dyspnea, eventually leading to right-sided heart failure. After a DVT, around one-third of patients will develop post-thrombotic syndrome with chronic lower-extremity edema, pain, and skin changes that can progress to weeping ulcerations. More than 20% of patients with proximal DVT (thrombus located in the popliteal, femoral, or iliac veins) or PE will suffer a recurrent event after discontinuing anticoagulation, and patients may experience loss of function, financial burdens from treatment, and fear of recurrence.

VTE risk factors

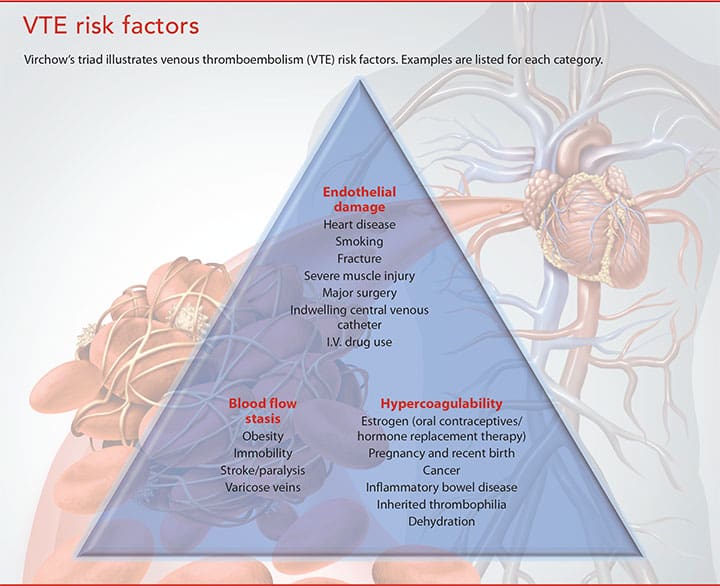

Virchow’s triad illustrates VTE risk factors based on blood flow stasis, endothelial damage, and hypercoagulability. (See VTE risk factors.) Normal venous return of blood from the extremities depends on the pumping action from the muscles and competent one-way valves in the vein. Reduced mobility can result in decreased blood return, and damaged valves can contribute to blood pooling in the distal extremities. Damage to the endothelial layer of the veins from trauma, I.V. catheters, or surgery initiates the coagulation cascade. In addition, inherited hypercoagulable disorders and other conditions—such as dehydration, inflammatory bowel disease, and cancer—can produce varying degrees of hypercoagulability.

Hospitalization is the most important risk factor for VTE. Surgery patients have long been considered at greater risk for VTEs, but recent evidence suggests that they develop equally between patients admitted for medical illness and those admitted for surgery. Overall risk factors include lung disease, prior VTE, family history of VTE, and older age.

Oncology patients are at particular risk for developing VTE because many cancers (pancreatic, lymphoma, brain, liver, leukemia, colorectal, and metastatic) produce a hypercoagulable state. Cancer is so often associated with VTE that the development of a VTE in a patient with no known risk factors may warrant screening for occult cancers. A systematic literature review by van Es and colleagues noted that cancer was found in one in 20 patients within a year of developing an unprovoked (no known risk factor) VTE, with rates seven times higher in patients age 50 years and older. In addition, many patients with cancer are less mobile and have vascular catheters, compounding their risk.

Commitment to prevention

Thromboprophylaxis for at-risk hospitalized patients can reduce VTE by 30% to 65%, has a low incidence of major bleeding complications, and is cost-effective. However, despite widely published guidelines, public reporting, and incremental payment withholding for VTE, prevention recommendations remain largely underused. Because VTE risk factors are spread across patient populations and medical specialties, no one group takes responsibility for addressing prevention; “everyone’s problem” becomes “no one’s problem.” Passive approaches, such as relying on staff and provider education or order sets have not proven effective.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) recommends “measure-vention” to boost compliance with adequate prophylaxis and to reduce rates of hospital-acquired VTE. This approach involves active measurement of adherence to and lapses in VTE prevention recommendations, combined with concurrent interventions to correct lapses, including notification of the primary team. The principles of prevention efforts are:

- institutional support and prioritization for the initiative

- a multidisciplinary team focused on reaching VTE prophylaxis targets and reporting to key medical staff committees

- reliable data collection and performance tracking

- specific goals or aims that are ambitious, time defined, and measurable

- proven quality improvement frameworks to coordinate steps toward breakthrough improvement

- evidence-based protocols that standardize VTE risk assessment and prophylaxis

- institutional infrastructure, policies, practices, and educational programs that promote use of the protocol.

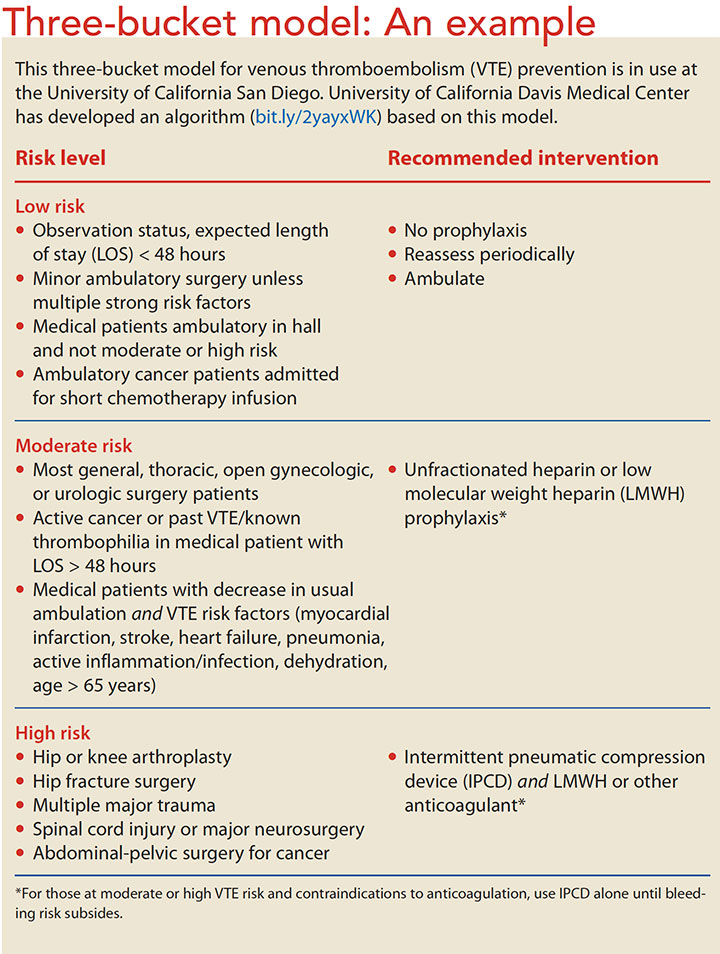

A three-bucket model based on risk level (low, moderate, high) may be an effective protocol. (See Three-bucket model: An example.) Protocols should be “opt-out” because nearly all hospitalized patients are at risk for developing VTE. In this model, mechanical and pharmaceutical interventions are activated for all patients, with those considered low risk or with contraindications to preventive measures “opted out.” Patients considered to be low risk in this model can ambulate independently and have no other risk factors.

Treatment recommendations

Guidelines published and regularly updated by the American College of Chest Physicians provide recommendations for the choice and duration of anticoagulant therapy to treat VTE, modified based on underlying risk factors. For patients with a PE or proximal DVT, a minimum course of 3 months of anticoagulant therapy is recommended. For patients with underlying cancer, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is preferable. For all other patients, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs, also called NOACs [nonvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants]) are preferred over vitamin K antagonist therapy. Dabigatran and edoxaban require initial parenteral anticoagulation. After completing the initial 3 months of treatment, patients with transient risk factors, such as surgery, typically don’t need additional therapy. For patients with unprovoked VTE, the provider should evaluate the risks and benefits of continued therapy. Most patients with active cancer will need to continue therapy.

Anticoagulants

Anticoagulants are indicated for the prevention and treatment of VTE. Understanding anticoagulant options will help when educating patients and monitoring for adverse effects. Keep in mind that all anticoagulants carry the risk of bleeding, so monitor for and immediately report any unusual bleeding.

Parenteral anticoagulants

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) and newer LMWHs are the parenteral agents used. UFH was the first parenteral anticoagulant; approved in 1939, it’s indicated for VTE prevention and treatment. It can be administered as a subcutaneous injection or I.V. infusion. Patients receiving a continuous infusion should have their partial thromboplastin time (PTT) monitored and dosage adjusted to maintain a PTT 1.5 to 2 times normal range. Most hospitals have a protocol for monitoring and adjusting heparin infusions. Protamine sulfate is the reversal agent.

The LMWH enoxaparin is indicated for DVT prevention in patients who’ve had abdominal surgery or hip or knee replacement. It’s also indicated for patients whose mobility is severely restricted because of acute illness and for treatment of acute DVT, with or without PE. Protamine sulfate is the reversal agent. Other LMWHs approved in the United States include dalteparin and tinzaparin.

When administered subcutaneously, both UFH and LMWH are injected into the abdomen. Hold a skinfold between the thumb and index finger throughout the injection, and don’t rub the site.

Oral anticoagulants

Warfarin has been the mainstay of oral anticoagulants for many years, but several new agents have been approved, including DOACs.

The vitamin K antagonist warfarin was approved in 1954. Because warfarin takes several days to become effective, it’s generally not used for immediate VTE prevention. Although relatively inexpensive and effective, warfarin requires lab monitoring of the patient’s international normalized ratio (INR) and frequent dose adjustments to maintain its narrow therapeutic range. Dosing is further complicated by metabolism variations based on DNA variants in two genes: CYP2C9 and VKORC1. Dosing algorithms are available based on genetic data. Warfarin can be affected by many other medications and foods. It can be reversed with vitamin K.

DOACs address some of the issues surrounding warfarin; for instance, they don’t require routine monitoring and have fewer drug interactions. A downside is that they’re more expensive than warfarin.

Recent studies suggest similar efficacy rates between warfarin and DOACs. Risks of bleeding appear similar, possibly favoring some of the DOACs over warfarin, even though no reversal agents are available, except for dabigatran. Extensive clinical trials have provided information on the safety and efficacy of DOACs in study populations; specifically, younger and healthier subjects. Postmarketing observational studies involving real-world, older individuals with more comorbidities have been performed primarily in patients with atrial fibrillation taking DOACs because they were approved for that indication before approval for VTE prevention and treatment.

Several DOACs have been approved for VTE prevention, including one that is a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran) and four that are factor Xa inhibitors (apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and betrixaban). Dosages must be adjusted for factors such as decreased creatinine clearance and whether the intention is treatment or prevention.

Dabigatranis indicated for VTE prevention in patients after hip replacement, treatment of VTE after 5 to 10 days of parenteral anticoagulation, and recurrent VTE reduction. Side effects include GI upset. Idarucizumab is the reversal agent.

Rivaroxabanand apixabanare indicated for DVT prevention in patients who’ve had hip or knee replacement, VTE treatment, and recurrence reduction. Patients should avoid concomitant use of rivaroxaban with drugs that are combined P-gp and strong CYP3A4 inducers (for example, carbamazepine, phenytoin, rifampin, and St. John’s wort). Menorrhagia and longer periods have been reported with rivaroxaban use. Andexanet alfa has been approved as a reversal agent for rivaroxaban and apixaban, although its supply is expected to be limited until early 2019.

Edoxabanis indicated for VTE treatment and has no reversal agent.

Betrixabanis indicated for VTE prophylaxis in adult patients hospitalized for an acute medical illness who are at risk for thromboembolic complications because of moderately or severely restricted mobility and other VTE risk factors. It has no reversal agent.

Anticoagulants and discharge

At discharge, provide patients with verbal instructions and supplemental written information about all medications—generic and trade names, dosage, frequency, possible food or drug interactions, and precautions—follow-up appointments, including lab monitoring, and signs and symptoms they should report. Explain the importance of continuing treatment beyond discharge and that patients shouldn’t stop anticoagulant therapy without discussing it with their provider. In addition, you can direct patients to resources to help cover the cost of anticoagulant therapy.

Nursing implications

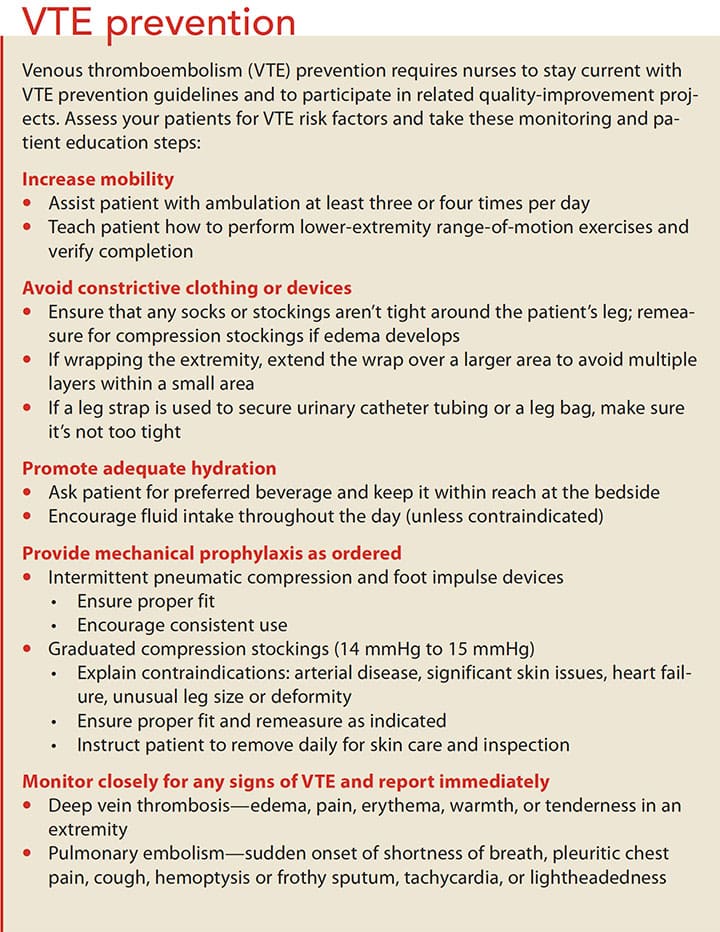

In addition to administering prophylaxis as ordered by the provider, you can help reduce your patient’s risk of developing a VTE. (See VTE prevention.) Patients are more likely to engage in prevention measures if they’re educated about their individual VTE risk factors, appreciate the consequences of a VTE, and understand the effectiveness of preventive measures.

Maintain and improve you patient’s mobility level by helping him or her walk to the bathroom, sit in a chair for meals, and walk in the hall with assistance. You also can teach your patient how to perform lower-extremity range-of-motion exercises and the rationale for compression stockings or lower-extremity mechanical devices. Remind patients to reapply devices after walking, and consistently reinforce your efforts. In addition, ensure patients are well hydrated; dehydration can contribute to hypercoagulability.

Even with preventive measures in place, VTE can develop. Early identification and treatment with anticoagulants can minimize serious long-term consequences.

Immediately report any signs and symptoms of a VTE. DVT symptoms can be subtle, so continually monitor for edema, pain, erythema, warmth, or tenderness in an extremity. Although DVTs typically are unilateral, also evaluate for bilateral symptoms. PE symptoms may be more dramatic, but still nonspecific. Suspect a PE in any patient with a sudden onset of shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, cough, hemoptysis or frothy sputum, tachycardia, or lightheadedness. These symptoms can be very distressing for the patient, so reassure him or her that the condition is being addressed and provide emotional support.

Administer treatment for VTE, such as anticoagulants, as instructed, and monitor for adverse effects.

Laying a foundation

Understanding VTE risk factors, prevention measures, and treatment options gives you a foundation for effectively engaging with patients and their families. Provide them with the information they’ll need to prevent VTE and to recognize signs and symptoms if they occur.

Carolyn E. Crumley is an adjunct assistant professor and clinical nurse specialist program coordinator at the University of Missouri-Columbia. She’s also a wound, ostomy, and continence nurse at Saint Luke’s East Hospital in Lee’s Summit, Missouri.

Selected References

D’Alesandro M. Focusing on lower extremity DVT. Nursing. 2016;46(4):28-35.

Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-53.

Heit JA, Spencer FA, White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):3-14.

Jenkins IH, White RH, Amin AN, et al. Reducing the incidence of hospital-associated venous thromboembolism within a network of academic hospitals: Findings from five University of California medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(suppl 2):S22-8.

Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-52.

Maynard G. Preventing hospital-associated venous thromboembolism: A guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed. AHRQ Publication No. 16-0001-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Reviewed August 2016. ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/patient-safety-resources/resources/vtguide/index.html

Office of the Surgeon General. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General.

Patel K, Fasanya A, Yadam S, Joshi AA, Singh AC, DuMont T. Pathogenesis and epidemiology of venous thromboembolic disease. Crit Care Nurse Q. 2017;40(3):191-200.

van Es N, Le Gal G, Otten HM, et al. Screening for occult cancer in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(6):410-7.

16-21 CE

2 Comments.

Thanks! Great article

I am looking for a reference list for this article on VTE.

https://www.myamericannurse.com/venous-thromboembolism-troubling-events/

Is it possible to obtain reference list?

Thank you.

Cathy.